Nepal

Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal | |

|---|---|

| Motto: जननी जन्मभूमिश्च स्वर्गादपि गरीयसी (Sanskrit) Janani Janmabhumishcha Swargadapi Gariyasi "Mother and Motherland are Greater than Heaven" Other traditional mottos:

| |

| Anthem: सयौँ थुँगा फूलका (Nepali) Sayaun Thunga Phulka "Hundreds of Flowers" | |

Location of Nepal in dark green; territory claimed but controlled by India shown in light green | |

| Capital and largest city | Kathmandu[1] 28°10′N 84°15′E / 28.167°N 84.250°E |

| Official languages | Nepali[2] |

| Recognised national languages | 124 languages[3][4][5] |

| Ethnic groups (2021)[6] |

|

| Religion (2021)[7] |

|

| Demonym(s) | |

| Government | Federal parliamentary republic |

| Ram Chandra Poudel | |

| Ram Sahaya Yadav | |

| KP Sharma Oli | |

| Bishowambhar Prasad Shrestha | |

| Legislature | Federal Parliament |

| National Assembly | |

| House of Representatives | |

| Formation | |

| 25 September 1768[8] | |

| 4 March 1816 | |

| 21 December 1923 | |

| 28 May 2008 | |

| 20 September 2015 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 147,516 km2 (56,956 sq mi) (93rd) |

• Water (%) | 2.8% |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | 31,122,387[11] (49th) |

• Density | 180/km2 (466.2/sq mi) (72nd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2010) | 32.8[13] medium |

| HDI (2019) | medium (142nd) |

| Currency | Nepalese rupee (Rs, रू) (NPR) |

| Time zone | UTC+05:45 (Nepal Standard Time) |

| Date format | YYYY/MM/DD |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +977 |

| ISO 3166 code | NP |

| Internet TLD | .np |

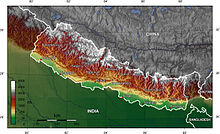

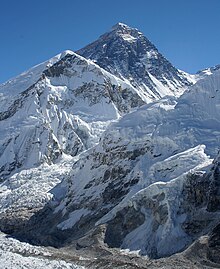

Nepal,[a] officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal,[b] is a landlocked country in South Asia. Mainly situated in the Himalayas, it also includes parts of the Indo-Gangetic Plain. It borders the Tibet Autonomous Region of China to the north, and India to the south, east, and west, while being narrowly separated from Bangladesh by the Siliguri Corridor, and from Bhutan by Sikkim. Nepal's geography is diverse, featuring the Himal region with its high mountains, the hilly Pahad region, and the fertile Terai plains. This varied topography includes eight of the world’s ten tallest mountains, including Mount Everest, the highest point on Earth. Kathmandu is the nation's capital and the largest city. Nepal is a multi-ethnic, multi-lingual, multi-religious, and multi-cultural state, with Nepali as the lingua franca and official language.

The name "Nepal" first appears in texts from the Vedic period of the Indian subcontinent. During ancient Nepal, Hinduism, the country's predominant religion, was established. In the first millennium BC, Gautama Buddha, the founder of Buddhism, was born in Lumbini in southern Nepal. Northern Nepal was influenced by Tibetese culture, while the Kathmandu Valley, known for its Newar confederacy called Nepal Mandala, was culturally tied to the Indo-Aryans. The valley’s traders dominated the Himalayan branch of the ancient Silk Road and developed unique traditional art and architecture.

By the 18th century, the Gorkha Kingdom unified Nepal, and the Shah dynasty established the Kingdom of Nepal. The country formed an alliance with the British Empire under the Rana dynasty of premiers. Nepal was never colonized but acted as a buffer state between Imperial China and British India.

In 1951, Parliamentary democracy was introduced but was suspended twice by monarchs, in 1960 and 2005. The Nepalese Civil War in the 1990s and early 2000s led to the establishment of a secular republic in 2008, ending the world's last Hindu monarchy. The Constitution of Nepal, adopted in 2015, declares the country a secular federal parliamentary republic with seven provinces. Nepal joined the United Nations in 1955, signed friendship treaties with India in 1950 and China in 1960, and hosts the permanent secretariat of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), of which it is a founding member. It is also a member of the Non-Aligned Movement and the Bay of Bengal Initiative.

Etymology

Before Nepal's unification, the term Nepal referred to the Kathmandu Valley. Over time, it came to denote both the valley and, at times, a larger area controlled by the Kathmandu monarch.[16] The origin of Nepāl remains unclear, though it appears in texts from the fourth century AD.[17] Various theories exist:

Hindu mythology suggests the name may come from the sage Ne, also known as Ne Muni or Nemi. According to the Pashupati Purāna, Nepal was named Nepāl as a place protected by this sage.[18]

In Buddhist mythology, the name might be linked to Manjushri Bodhisattva who drained a primordial lake to create the Nepal valley, naming it Nepāl after the deity Ne who would protect its settlers.[19]

According to the Gopalarājvamshāvali, Nepal is named after Nepa, a cowherd who discovered the Jyotirlinga of Pashupatināth. The cow that helped him was also named Ne.[20]

Early European scholars, such as William Kirkpatrick and Francis Buchanan-Hamilton, dismissed local myths as folklore.[21] Christian Lassen proposed that Nepāla means "abode at the foot of the mountain".[22] Sylvain Lévi found Lassen's theory untenable but suggested that Nepāla might be a Sanskritisation of local terms or a Tibeto-Burman root meaning "cattle keeper".[23][24]

History

Ancient Nepal

Ancient Nepal's history dates back to the arrival of modern humans around 55,000 years ago. The earliest known settlements in Nepal emerged approximately 30,000 years ago. By 4000 BC, Tibeto-Burmese people migrated into the region, followed by Indo-Aryans. The Gopal Bansa was the first recorded dynasty, succeeded by the Kiratas, who ruled for over 16 centuries. By 600 BC, small kingdoms formed, including the Shakya, from which Gautama Buddha emerged (traditionally dated 563–483 BC)[25]. By 250 BC, the Maurya Empire influenced the area, with Emperor Ashoka visiting Lumbini and erecting a pillar marking Buddha's birthplace[26]. The Licchavi dynasty rose around 400 AD, leaving extensive inscriptions that inform much of Nepal's history[27]. Following their decline, the Thakuri dynasty ruled until the 11th century[28].

Medieval Nepal

In the 11th century, a powerful empire of Khas people emerged in western Nepal, extending into western Tibet and Uttarakhand. By the 14th century, the empire had fragmented into the Baise Rajyas, or 22 states. The Khas people's language evolved into modern Nepali, becoming the lingua franca of Nepal and parts of North-east India.[29]

- 1097 CE: The Simroun Dynasty was founded with its capital at Simroungarh (modern Bara district). It controlled Tirhut (Mithila) in Nepal and Bihar and ruled for over 200 years, even influencing Kathmandu temporarily.[30]

- 1324 CE: The kingdom fell to Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq. Harisingh Dev, the last ruler, fled north, and his son Jagatsingh Dev married Nayak Devi, a princess from Bhaktapur.[31][32]

- 14th Century: The Mallas established themselves in Kathmandu and Patan, initially under the suzerainty of Tirhut. By the late 14th century, they became independent.[29]

- Late 14th Century: Jayasthiti Malla introduced significant reforms, including the caste system, which influenced the Sanskritization and Hinduization of Nepalese society.

- 15th Century: Kathmandu evolved into a powerful empire, extending from Tibet to India. By the late 15th century, the Malla kingdom was divided into Kathmandu, Patan, Bhaktapur, and Banepa. This division led to the flourishing of art and architecture, including the renowned Kathmandu, Patan, and Bhaktapur Durbar Squares.[29][33]

- 18th Century: Prithvi Narayan Shah of the Shah dynasty sought to unify the fragmented principalities. His conquests began with Nuwakot in 1744 and extended to Kathmandu by 1768.[34]

- 1768 CE: Shah's forces conquered Kathmandu during the festival of Indra Jatra, leading to the fall of the Malla rulers. He declared Kathmandu as the capital of the Kingdom of Nepal, marking the beginning of a unified Nepal.[35]

Medieval Nepal saw the rise and fall of significant dynasties and principalities, including the Khas Empire, Simroun Dynasty, and Malla Dynasty. The Malla period was marked by cultural and architectural advancements, while the Shah dynasty's unification efforts established modern Nepal.

Unification and expansion (1768–1846)

In the mid-18th century, Prithvi Narayan Shah, a Gorkha king, set out to unify what is now Nepal. He first secured neutrality from neighboring mountain kingdoms and, after significant battles including the Battle of Kirtipur, conquered the Kathmandu Valley by 1769[36].

Nepal's reach extended to Kumaon, Garhwal, and Sikkim. Disputes with Tibet over mountain passes and inner Tingri valleys led to the Sino-Nepalese War, forcing Nepal to retreat from these areas[37]. The rivalry with the East India Company led to the Anglo-Nepalese War (1815–16). Initially underestimated, the Nepali forces proved formidable, but the war ended with the Sugauli Treaty, under which Nepal ceded several territories[38].

Rana dynasty (1846–1951)

The dynasty saw modernization efforts like infrastructure projects but was also marked by severe repression. The Shumsher branch, starting in 1885, maintained this autocratic rule until the People's Movement of 1951 restored a constitutional monarchy. Key reforms included banning Sati in 1919 and abolishing Kamaiya (slavery) in 1924[39][40].

Birth of democracy (1951–1960)

In 1951, the Nepali Congress overthrew the Rana regime[41], ushering in democracy and B.P. Koirala as the first democratically elected Prime Minister[42]. However, in 1960, King Mahendra dissolved democratic institutions and introduced the Panchayat system, a partyless regime. Political leaders were exiled or imprisoned, while a communist insurgency in the 1970s was swiftly suppressed[43].

Panchayat era (1960–1990)

The Panchayat era began when King Mahendra dissolved the Nepali Congress government on 15 December 1960 and established the Panchayat system on 5 January 1961, centralizing power and banning political parties[44].

Reforms included land redistribution and the Mahendra Highway, but the regime faced growing criticism for its authoritarianism. Economic issues and public dissent led to the People's Movement of February 1990, which ended the Panchayat system and restored multiparty democracy[45].

Return of democracy, civil war and peace (1990-2008)

In April 1990, the Jana Andolan[46] ended the Panchayat system and restored democracy, leading to the 1990 Constitution.

The Maoist insurgency, starting on 13 February 1996, resulted in over 17,000 deaths and ended with the Comprehensive Peace Accord on 21 November 2006[47].

The 2001 royal massacre[48] and King Gyanendra’s 2005 coup d'état[49] led to political instability. The Loktantra Andolan, beginning in April 2006, abolished the monarchy on 28 May 2008 and established a federal democratic republic[50].

Contemporary history (2008-present)

On 28 May 2008, Nepal abolished the monarchy[51] and became a federal democratic republic. The constitution adopted on 20 September 2015[52] established a secular state with seven provinces and a bicameral parliament but faced criticism from various groups.

The 25 April 2015 earthquake[53] killed nearly 9,000 and caused extensive damage. Recovery was delayed by the 2015 Nepal blockade[54], an unofficial blockade by India.

Since then, Nepal has faced political instability but continues to work on recovery, development, and economic growth while striving for democratic stability.

Geography

Nepal is a landlocked country situated between China and India, measuring about 800 km long and 200 km wide, with an area of 147,516 km2. Its defining geological processes began 75 million years ago when the Indian plate drifted northeastward, causing the Indian crust to under-thrust Eurasia and uplift the Himalayas.[55]

Nepal is divided into three physiographic belts: Himal (mountains), Pahad (hills), and Terai (plains). The Himal region contains the world's highest peaks, including Mount Everest (8,848 m) on the China border.[56] The Pahad region consists of mountains ranging from 800 to 4,000 m, while the Terai plains in the south are part of the Indo-Gangetic Plain.

The Indian plate continues to move north at about 50 mm per year, making Nepal prone to earthquakes that present significant development challenges.[57] Erosion of the Himalayas is a major source of sediment flowing to the Indian Ocean.[58] Severe flooding and landslides during the monsoon season cause deaths, destroy farmlands, and damage infrastructure.

Climate

Nepal has five climatic zones, broadly corresponding to the altitudes. The tropical and subtropical zones lie below 1,200 metres (3,900 ft), the temperate zone 1,200 to 2,400 metres (3,900 to 7,900 ft), the cold zone 2,400 to 3,600 metres (7,900 to 11,800 ft), the subarctic zone 3,600 to 4,400 metres (11,800 to 14,400 ft), and the Arctic zone above 4,400 metres (14,400 ft). Nepal experiences five seasons: summer, monsoon, autumn, winter and spring. The Himalayas block cold winds from Central Asia in the winter and form the northern limits of the monsoon wind patterns.

Biodiversity and conservation

Nepal has a disproportionately high diversity of plants and animals relative to its size.[60][61] The country forms the western part of the eastern Himalayan biodiversity hotspot and features significant biocultural diversity.[62] Nepal's varied elevations (from 60 m in the Terai plains to 8,848 m at Mount Everest)[63] create diverse biomes.[60] The eastern part of Nepal, with more rainfall, is richer in biodiversity compared to the western regions, which have more arctic desert-type conditions.[61] Nepal hosts 4.0% of global mammal species, 8.9% of bird species, 1.0% of reptile species, 2.5% of amphibian species, 1.9% of fish species, 3.7% of butterfly species, 0.5% of moth species, and 0.4% of spider species.[61] It includes 2% of flowering plant species, 3% of pteridophytes, and 6% of bryophytes.[61]

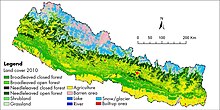

Nepal's forest cover is 59,624 km2 (23,021 sq mi), covering 40.36% of the country's total land area, with an additional 4.38% of scrubland, for a total forested area of 44.74%. This represents a 5% increase since the early 2000s.[64] In 2019, Nepal had a Forest Landscape Integrity Index score of 7.23/10, ranking it 45th out of 172 countries.[65] The southern plains, Terai–Duar savanna and grasslands ecoregion contains tall grasses, Sal forests, tropical evergreen forests, and tropical riverine deciduous forests.[66] The lower hills (700–2,000 m) feature subtropical and temperate deciduous mixed forests with species like Sal, Chilaune, and Katus, while subtropical pine forests are dominated by chir pine. The middle hills (2,000–3,000 m) are known for oak and rhododendron, and above 3,500 m in the west and 4,000 m in the east, alpine shrubs and meadows take over.[61]

Among the notable trees are the astringent Azadirachta indica, or neem, which is widely used in traditional herbal medicine,[67] and the luxuriant Ficus religiosa, or peepal,[68] which is displayed on the ancient seals of Mohenjo-daro,[69] and under which Gautam Buddha is recorded in the Pali canon to have sought enlightenment.[70]

Most of the subtropical evergreen broad-leaved forest of the lower Himalayan region is descended from the Tethyan Tertiary flora.[72] As the Indian Plate collided with Eurasia forming and raising the Himalayas, the arid and semi-arid Mediterranean flora was pushed up and adapted to the more alpine climate over the next 40–50 million years.[72][73] The Himalayan biodiversity hotspot was the site of mass exchange and intermingling of the Indian and Eurasian species in the neogene.[74] One mammal species (Himalayan field mouse), two each of bird and reptile species, nine amphibia, eight fish and 29 butterfly species are endemic to Nepal.[61][c]

Nepal is home to 107 IUCN-designated threatened species, including 88 animals, 18 plants, and one fungi or protist species.[76] These include endangered species such as the Bengal tiger, red panda, Asiatic elephant, Himalayan musk deer, wild water buffalo, and South Asian river dolphin,[77] as well as critically endangered species like the gharial, Bengal florican,[60][78] and white-rumped vulture, which has been nearly wiped out due to diclofenac-treated cattle carrion.[79]

To combat the threats, Nepal has expanded its Protected areas of Nepal since 1973. Efforts include vulture restaurants, a ban on diclofenac, and breeding programs,[80][81] which, along with community-assisted patrols,[82] has reduced poaching to nearly zero and increased populations of tigers, elephants, and rhinos.[83]

Nepal has ten national parks, three wildlife reserves, one hunting reserve, three Conservation Areas, and eleven buffer zones, covering 28,959.67 km2 (11,181.39 sq mi) (19.67% of the total land area),[84] and ten wetlands are listed under the Ramsar Convention.[85]

Ecology

Nepal has consistently ranked among the most polluted countries globally, particularly due to high levels of PM2.5. In 2019, it had the second highest PM2.5 concentration, averaging 83.1 μg/m³, according to the State of Global Air report. Recent data indicates that Kathmandu frequently tops air quality rankings, with PM2.5 levels soaring to 258 μg/m³, exacerbated by factors like forest fires and lack of rainfall. This persistent pollution poses severe health risks, contributing to thousands of premature deaths annually and highlighting the urgent need for effective air quality management strategies in the region . [86][87][88][89][90][91][92]

Government and politics

Nepal is a federal democratic republic divided into seven provinces, each with its own provincial government. Additionally, the country is further decentralized into 753 local governments, which include municipalities and rural municipalities. This structure allows for a high degree of local governance and administrative efficiency, reflecting Nepal's commitment to federalism and regional autonomy. The Constitution of Nepal outlines the roles and responsibilities of these various levels of government, ensuring that power is distributed across different tiers and that local needs and interests are adequately addressed.[93][94][95][93][96][97][98][99][100]

National government

Nepal is governed by the Constitution of Nepal, which establishes it as a multi-ethnic, multi-lingual, and multi-cultural nation committed to national independence and territorial integrity.[4]

The Government of Nepal has three branches:[4]

- Executive: Governed by a multi-party federal democratic republican system. The President appoints the Prime Minister from the majority party in the House of Representatives, who then forms the Council of Ministers.

- Legislature: The Federal Parliament consists of the House of Representatives (275 members elected through a mixed electoral system) and the National Assembly (59 members elected by provincial electoral colleges). The House has a five-year term, while the National Assembly has staggered six-year terms.[101]

- Judiciary: Nepal has a three-tier independent judiciary, including the Supreme Court, seven High Courts, and 77 district courts. Local councils can establish judicial bodies for non-binding dispute resolution.[4]

Political parties

Nepal has a multi-party system with several significant national parties. The major national parties currently represented in the federal parliament are:

| Party | Abbreviation | Ideology | Seats in Federal Parliament |

|---|---|---|---|

| Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist–Leninist) | CPN(UML) | Leftist | 44[93] |

| Nepali Congress | NC | Centrist | 89[93] |

| Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist Centre) | CPN (Maoist Centre) | Leftist | 32[93] |

| Rastriya Swatantra Party | RSP | Centrist | 20[93] |

| Rastriya Prajatantra Party | RPP | Right-wing | 14[93] |

| People's Socialist Party, Nepal (2020) | PSP-N | Socialist | 17[93] |

| Janamat Party | JP | Socialist | 6[93] |

Subdivisions

| Province | Capital | Districts | Area (km2) |

Population Census 2011 |

Population Census 2021 |

Density (people/km2) 2021 |

Human Development Index |

Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Koshi Province | Biratnagar | 14 | 25,905 | 4,534,943 | 4,972,021 | 192 | 0.553 |

|

| Madhesh Province | Janakpur | 8 | 9,661 | 5,404,145 | 6,126,288 | 634 | 0.485 |

|

| Bagmati Province | Hetauda | 13 | 20,300 | 5,529,452 | 6,084,042 | 300 | 0.560 |

|

| Gandaki Province | Pokhara | 11 | 21,856 | 2,403,757 | 2,479,745 | 113 | 0.567 |

|

| Lumbini Province | Deukhuri | 12 | 19,707 | 4,499,272 | 5,124,225 | 260 | 0.519 |

|

| Karnali Province | Birendranagar | 10 | 30,213 | 1,570,418 | 1,694,889 | 56 | 0.469 |

|

| Sudurpashchim Province | Godawari | 9 | 19,539 | 2,552,517 | 2,711,270 | 139 | 0.478 |

|

| Nepal | Kathmandu | 77 | 147,181 | 26,494,504 | 29,192,480 | 198 | 0.579 |

|

Nepal is a federal republic comprising 7 provinces, each with 8 to 14 districts. These districts include local units known as urban and rural municipalities.[4] There are 753 local units: 6 metropolitan municipalities, 11 sub-metropolitan municipalities, 276 municipalities, and 460 rural municipalities.[102] There are 6,743 wards in total.

Local governments have executive, legislative, and limited judicial powers. Provinces have unicameral parliamentary systems. Local and provincial governments share powers with the federal government. The district coordination committee, made up of elected officials from local governments, has a limited role.[4][102]

Law enforcement and crime

The Constitution of Nepal is the supreme law, invalidating any contradictory laws.[103] Legal provisions are codified in Civil and Criminal Codes, with the Supreme Court as the highest authority in law interpretation. The death penalty has been abolished,[104] and marital rape is recognized, alongside abortion rights, though constraints exist due to sex-selective abortion. Nepal is a signatory to various international treaties, including the Geneva Convention and Chemical Weapons Convention. Some legal provisions remain discriminatory, particularly against foreign nationals married to Nepali citizens.[d] Paternal lineage is valued in legal documents, and many laws are unenforced.

The Nepal Police is the main law enforcement agency, operating independently under the Inspector General. It maintains law and order and manages road traffic. The Armed Police Force assists with crowd control and internal security. The Crime Investigation Department specializes in criminal investigations.[106][107] The Commission for the Investigation of Abuse of Authority investigates corruption and abuse of power.

Nepal's intentional homicide rate was 2.16 per 100,000 in 2016, lower than average, but police data indicates a 40% increase in crime over the past five years.[108] Nepal ranked 76 out of 163 countries in the Global Peace Index (GPI) in 2019.[109] The Nepali passport is among the weakest globally.[110]

Foreign relations

Nepal relies on diplomacy for national defense, maintaining a neutral stance between its neighbors. It has amicable relations with regional countries and adheres to a non-alignment policy globally. Nepal is a member of organizations like SAARC, UN, and WTO, with diplomatic ties to 167 countries and the EU,[111] and embassies in 30 countries.[112]

Nepal is a significant contributor to UN peacekeeping missions, having deployed over 119,000 personnel since 1958.[113] The Gurkhas have a storied history in the British and Indian armies, recognized for their bravery.

Nepal maintains balanced relations with India and China. The 1950 Treaty of Peace and Friendship with India fosters close ties, allowing free movement and property ownership across borders.[114] However, territorial disputes and economic issues have strained relations. Nepal established diplomatic ties with China in 1955, signing the Treaty of Peace and Friendship in 1960, and adheres to the One China Policy.[115]

Nepal emphasizes cooperation in South Asia, being a founding member of SAARC. It recognized an independent Bangladesh early on and seeks to enhance trade and water management ties.[116] Nepal was also the first South Asian nation to establish diplomatic relations with Israel, balancing its recognition of Palestinian rights.[117]

Nepal enjoys strong relationships with major donors and development partners, including the US, UK, Japan, and Norway, which support its development goals.[118]

Military

The President is the supreme commander of the Nepali Army; its routine management is handled by the Ministry of Defence. The military expenditure for 2018 was $398.5 million,[119] around 1.4% of GDP.[120] An almost exclusively ground infantry force, the Nepal Army numbers less than one hundred thousand;[121][122][123] recruitment is voluntary.[124] It has few aircraft, mainly helicopters, primarily used for transport, patrol, and search and rescue.[125] The Directorate of Military Intelligence under the Nepal Army serves as the military intelligence agency;[126] the National Investigation Department, tasked with national and international intelligence gathering, is independent.[121] The Nepal Army is primarily used for routine security of critical assets, anti-poaching patrols of national parks, counterinsurgency, and search and rescue during natural disasters;[127] it also undertakes major construction projects.[128] There are no discriminatory policies on recruitment into the army, but it is dominated by men from elite Pahadi warrior castes.[129][130]

Economy

Nepal is one of the least developed countries, ranking 165th in the world[e] in nominal GDP per capita[131] and 162nd[f] in GDP per capita at PPP.[132]

Nepal’s economy is primarily based on agriculture, which contributes approximately 27% to the country’s GDP. The service sector, including tourism, accounts for around 57% of GDP, while industry and manufacturing contribute about 16%[133].

The country faces several economic challenges, including political instability, inadequate infrastructure, and reliance on remittances from abroad, which form a significant part of the economy. However, there have been improvements in recent years with initiatives aimed at boosting tourism and improving trade and industry.

The government has also implemented policies to support the economic growth of the country, including efforts to enhance agricultural productivity, promote industrialization, and expand infrastructure projects.

Tourism

Tourism is one of Nepal's largest industries, employing over a million people and contributing 7.9% to the GDP.[134] In 2018, international visitors surpassed one million for the first time (excluding Indian tourists arriving by land).[134] Nepal captures about 6% of visitors to South Asia but only 1.7% of the earnings.[135] Key destinations include Pokhara, the Annapurna trekking circuit, and four UNESCO World Heritage sites: Lumbini, Sagarmatha National Park, and Chitwan National Park. Most mountaineering revenue comes from Mount Everest, which is more accessible from Nepal.[136]

Nepal opened to westerners in 1951 and gained popularity in the 1960s and 1970s as part of the hippie trail.[137] The industry has faced challenges, including infrastructure bottlenecks and issues with Nepal Airlines. However, home-stay tourism has seen some success.[138]

Everest tourism

Mount Everest, the highest peak in the world, is a major attraction for both climbers and trekkers. The Everest region, known as the Khumbu, includes the famous Everest Base Camp trek, which draws thousands of adventure seekers annually. Climbing permits for Everest generate substantial revenue for the government, and the tourism associated with Everest supports the local economy, particularly in the towns of Namche Bazaar and Lukla. Despite the allure, Everest tourism has been criticized for contributing to environmental degradation and overcrowding.[139]

Foreign employment

Unemployment and underemployment affect over half of the working-age population,[140] prompting millions to seek work abroad, mainly in India, the Gulf, and East Asia. Many workers are unskilled and indebted, often falling victim to exploitation and fraud.[141] Their passports are often seized, and most do not receive minimum wage.[142]

Many work in unsafe conditions, with an average of two workers dying each day.[143] Women often rely on traffickers to leave the country, leading to violence and abuse.[144]

Remittances are vital for many families, reaching approximately USD 11 billion in 2023, accounting for over 26% of Nepal's GDP. However, the reliance on remittances poses challenges for sustainable income and productive use of funds.

- Remittances grew from $5.87 billion in 2014 to $11 billion in 2023, an 87% increase.

- A dip in 2020 due to COVID-19 was followed by a rebound in 2021.

- Remittances are crucial for stabilizing the economy and reducing poverty.

- The upward trend in remittances highlights their importance for Nepalese livelihoods.

Science, technology and energy

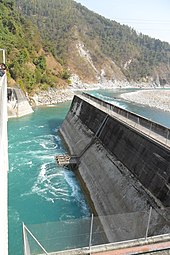

Energy in Nepal primarily comes from biomass (80%) and imported fossil fuels (16%).[145] The residential sector consumes 84% of energy, while transport and industry account for 7% and 6%, respectively.[145] Nepal lacks significant oil, gas, or coal deposits, relying on imports for fossil fuels, which consume 129% of total export revenue.[146] Only about 1% of energy needs are met by electricity, despite the country's estimated hydroelectric potential of 42,000 MW; currently, only 1,100 MW is utilized.[145] Nepal imports up to 650 MW from India to meet peak demands.[147] Nepal's electrification rate is 76%, with significant disparities between rural (72%) and urban (97%) areas.[145] The energy sector faces challenges such as high tariffs, system losses, and insufficient domestic demand.[148] According to the Nepal Telecommunication Authority MIS August 2019 report, the voice telephony subscription rate was 2.70% for fixed phones and 138.59% for mobile phones, with 98% of voice telephony being mobile.[149] Approximately 14.52% had access to fixed broadband, and 52.71% accessed the internet via mobile data, with nearly 15 million using 3G or better.[149] The mobile market is dominated by Nepal Telecom (55%) and Ncell (40%).[149] Despite disparities, mobile service covers 90% of the land area, with broadband access expected to reach 90% of the population by 2020.[150]

Transportation

Nepal is largely isolated from major transport routes, but aviation is relatively developed, with 47 airports, 11 of which have paved runways.[150] As of 2016, there were over 11,890 km of paved roads and 16,100 km of unpaved roads, with only 59 km of railway.[150]

Most rural roads become impassable during the rainy season, and Nepal relies heavily on assistance from countries like China and India for infrastructure development. The only practical seaport for goods bound for Kathmandu is Kolkata in India. The national carrier, Nepal Airlines, faces challenges due to mismanagement and has been blacklisted by the EU.[151]

Access to markets and services is hindered by poor road conditions, with Nepal having one of the worst road infrastructures in Asia.[152]

Public transportation is primarily by bus, with options ranging from local to long-distance services. Tourist buses connect major destinations like Kathmandu and Pokhara, offering more comfort than local buses. Air travel is crucial for accessing remote areas, with Tribhuvan International Airport serving as the main hub.

Despite challenges, transportation options are improving, with initiatives to enhance road networks and air travel accessibility.

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1911 | 5,638,749 | — |

| 1920 | 5,573,788 | −0.13% |

| 1930 | 5,532,574 | −0.07% |

| 1941 | 6,283,649 | +1.16% |

| 1952/54 | 8,256,625 | +2.51% |

| 1961 | 9,412,996 | +1.47% |

| 1971 | 11,555,983 | +2.07% |

| 1981 | 15,022,839 | +2.66% |

| 1991 | 18,491,097 | +2.10% |

| 2001 | 23,151,423 | +2.27% |

| 2011 | 26,494,504 | +1.36% |

| 2021 | 29,192,480 | +0.97% |

| Source:Census in Nepal | ||

Nepal is a diverse country with 142 recognized ethnic groups, 124 mother tongues, and 10 major religions according to the 2021 Census. The largest ethnic groups include Chhetri (16.45%), Brahmin-Hill (11.29%), and Magar (6.9%). Nepali remains the most widely spoken language at 44.86%, followed by Maithili (11.05%) and Bhojpuri (6.24%). Hinduism is the dominant religion, with 81.19% of the population identifying as Hindu, while Buddhism (8.21%) and Islam (5.09%) are the next largest faiths. The population of Nepal reached 31,240,315 as of July 1, 2024, with a population density of 212.26 people per square kilometer. The annual population growth rate has declined from 2.25% in 2001 to 1.35% in 2011. The median age in Nepal is 24.79 years, and the fertility rate is projected to reach 1.6868 births per woman by 2100. Despite the diversity, Nepal's political and socio-cultural representation remains heavily skewed towards dominant caste groups. Marginalized communities continue to face exclusion and persecution, with limited representation in the legislature, government, and civil service.[153]

Urbanization

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Kathmandu  Pokhara |

1 | Kathmandu | Bagmati | 845,767 | 11 | Janakpur | Madhesh | 195,438 |  Bharatpur  Lalitpur |

| 2 | Pokhara | Gandaki | 518,452 | 12 | Butwal | Lumbini | 195,054 | ||

| 3 | Bharatpur | Bagmati | 369,377 | 13 | Tulsipur | Lumbini | 180,734 | ||

| 4 | Lalitpur | Bagmati | 299,843 | 14 | Budhanilkantha | Bagmati | 179,688 | ||

| 5 | Birgunj | Madhesh | 268,273 | 15 | Dharan | Koshi | 173,096 | ||

| 6 | Biratnagar | Koshi | 244,750 | 16 | Nepalgunj | Lumbini | 166,258 | ||

| 7 | Dhangadhi | Sudurpashchim | 204,788 | 17 | Birendranagar | Karnali | 154,886 | ||

| 8 | Ghorahi | Lumbini | 201,079 | 18 | Tarakeshwar | Bagmati | 151,508 | ||

| 9 | Itahari | Koshi | 198,098 | 19 | Gokarneshwar | Bagmati | 151,200 | ||

| 10 | Hetauda | Bagmati | 195,951 | 20 | Tilottama | Lumbini | 149,657 | ||

Ethnicity

Nepal's ethnic diversity is reflected in the 142 recognized ethnic groups as per the 2021 Census, an increase from 125 in 2011. The largest groups include Chhetri (16.45%), Brahmin-Hill (11.29%), and Magar (6.9%). The census also documented 124 mother tongues and 10 religions practiced in the country. This classification considers language, cultural identity, and the caste system, highlighting Nepal's complex social fabric and the significant presence of indigenous communities.

The Caste/Ethnic groups of Nepal that comprise more than 1% of the total population, according to the 2021 Census, are as follows:[155]

This data illustrates the rich ethnic diversity in Nepal, with a total of 142 ethnic groups identified in the latest census.

Language

Nepal's linguistic diversity is a reflection of its rich cultural mosaic. The country is home to languages from three major language families: Indo-Aryan, Sino-Tibetan, and various indigenous isolates.

Here is a pie chart showing the major languages of Nepal according to the 2021 Census:

Major languages of Nepal (2021 Census)

The chart shows that Nepali remains the most widely spoken language, with 44.86% of the population reporting it as their mother tongue. Maithili is the second largest at 11.05%, followed by Bhojpuri (6.24%), Tharu (5.88%), and Tamang (4.88%). The remaining languages each account for less than 5% individually, with the "Other" category comprising the combined share of the many smaller languages spoken across Nepal.

Religion

Nepal is a secular country, as declared by the Constitution of Nepal 2015 (Part 1, Article 4), where secularism 'means religious, cultural freedom, along with the protection of religion, culture handed down from time immemorial.[156][157]

The distribution of religions in Nepal based on the 2021 census is as follows:

Religion in Nepal (2021)[158]

Education

Nepal entered modernity in 1951 with a literacy rate of 5% and about 10,000 students enrolled in 300 schools.[159] By 2017, enrollment exceeded seven million in 35,601 schools, with a literacy rate increasing from 54.1% in 2001 to 65.9% in 2011. The net primary enrollment rate reached 97% by 2017,[160] but secondary enrollment was under 60% and tertiary enrollment around 12%.[161]

Challenges include inadequate infrastructure, high student-to-teacher ratios, and politicization of school management.[162] Free basic education is constitutionally guaranteed but lacks sufficient funding.[163] The government offers scholarships for girls, disabled students, and children from marginalized communities.[164]

Tens of thousands of Nepali students study abroad each year, with many not returning.[165]

Health

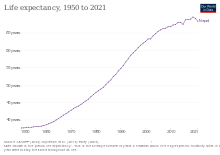

Health care services in Nepal are provided by both public and private sectors. As of 2017, life expectancy at birth was estimated at 71 years, up from 54 years in the 1990s and 35 years in 1950.[166] Two-thirds of all deaths are due to non-communicable diseases, with heart disease as the leading cause.[167] Many also suffer from communicable diseases due to poor sanitation and malnutrition.

Progress has been made in maternal and child health, with 95% of children having access to iodised salt and 86% receiving Vitamin A prophylaxis.[168] However, malnutrition remains high at 43% among children under five.[169] The maternal mortality rate has decreased to 229 per 100,000, down from 901 in 1990.[170]

Health initiatives include public health centers providing essential medicines and a health insurance plan covering treatments up to Rs 50,000 for families.[171] School meal programs have improved nutrition among children.[172]

Despite improvements, access to quality health care remains a challenge, particularly in rural areas, and many Nepali policymakers seek medical care abroad.[173]

Immigration

Nepal has a long tradition of accepting immigrants and refugees.[174] In modern times, the majority of refugees are Tibetans and Bhutanese. Tibetan refugees began arriving in 1959,[175] while Bhutanese Lhotsampa refugees started arriving in the 1980s, with over 110,000 by the 2000s, most of whom have been resettled in third countries.[176] As of late 2018, Nepal had around 20,800 confirmed refugees, predominantly Tibetan and Bhutanese.[177]

Economic immigrants and refugees from neighboring countries, Africa, and the Middle East, termed "urban refugees," lack official recognition and often live in cities instead of camps.[178] In 2018/19, around 2,000 immigrants, half of them Chinese, applied for work permits. The government lacks data on Indian immigrants, who do not require permits; the Government of India estimates around 600,000 Non-Resident Indians in Nepal.[179][180]

Culture and society

Nepali society is defined by a caste system, comprising over a hundred endogamous groups known as jātis. Despite the declaration of untouchability as illegal in 1963[181], caste discrimination persists, particularly affecting marginalized communities. Family values are significant, with arranged marriages common and a low divorce rate. Festivals like Gadhimai and Dashain involve large-scale animal sacrifices, raising concerns about animal welfare. Witch hunts continue to target vulnerable women, often resulting in violence and abuse.[182][183][184][185][186][187]

Festivals

- Dashain - Nepal's largest festival, lasting 15 days in October, celebrating Goddess Durga's victory over evil.

- Tihar - The festival of lights in November, honoring animals and sibling relationships.

- Maha Shivaratri - A Hindu festival in February or March honoring Lord Shiva with night vigils, especially at Pashupatinath.

- Buddha Jayanti - Celebrates the birth of Lord Buddha, observed in Lumbini and Buddhist sites.

- Gai Jatra - Commemorates deceased loved ones with processions and performances, mainly by the Newar community.

- Indra Jatra - Celebrated in September, honoring the rain god Indra, featuring the Kumari Jatra.

- Holi - The festival of colors, also known as Fagu Purnima.

- Janai Purnima - Hindu men renew their sacred thread on this full moon day.

- Maghe Sankranti - Celebrated in mid-January, marking the end of the cold season with festive meals.

Nepali festivals foster social cohesion, cultural heritage, and national participation.

Symbols

| |

| Emblem | Emblem of Nepal |

|---|---|

| Anthem | Sayaun Thunga Phulka |

| Currency | Nepalese rupee (रू) (NPR) |

| Bird | Himalayan monal |

| Flower | Rhododendron arboreum[189] |

| Mammal | Cow[188] |

| Colour | Crimson |

| Sport | Volleyball[190] |

The emblem of Nepal features the Himalayas, hills, and Terai, surrounded by rhododendrons, with a white map of Nepal and joined hands symbolizing gender equality. The national motto, "Mother and motherland are greater than heaven," is inscribed in Devanagari script.

Nepal's flag is unique, being the only non-rectangular national flag. The crimson color represents courage, while the blue border signifies peace. The moon symbolizes calmness, and the sun represents the valor of Nepali warriors.

The president symbolizes national unity, and martyrs represent patriotism. Notable figures like Prithvi Narayan Shah are regarded as national heroes.[191]

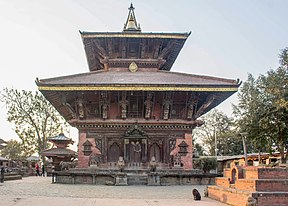

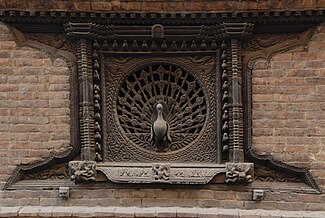

Architecture

Nepal's architecture features ancient stupas from the Buddhist period, including those built by Ashoka around 250 BC. The Kathmandu Valley's Newar artisans developed a distinctive style during the Lichchhavi period, known for its pagodas with intricate carvings and layered roofs.

Key structures include the Changu Narayan Temple and the Kathmandu, Patan, and Bhaktapur Durbar Squares. Traditional features include finely carved wooden elements and "ankhijhyal" windows, which provide one-way views.

Cultural looting remains a significant issue despite recovery efforts by organizations like the Nepal Heritage Recovery Campaign. Artifacts have been repatriated from major institutions and auctions worldwide, including the Art Institute of Chicago, Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Dallas Museum of Art.[192][193][194]

Literature

Nepali literature, written in Nepali, evolved from oral traditions and Sanskrit to modern works. Poet Bhanubhakta Acharya, known as the "Adikavi," was pivotal, translating the Ramayana into Nepali and producing original poetry.[195][196][197][198][199]

The early 20th century saw a revival with figures like Motiram Bhatta and a flourishing post-1960 era with writers such as Laxmi Prasad Devkota and Parijat. Following the 1991 democratic revolution, Nepali literature gained international prominence.[200][195]

Regional literatures in languages like Newar and Maithili are also developing, with Newar literature being the most prominent. However, these indigenous literatures face challenges in recognition and preservation.[195]

Mass Media

As of 2019[update], the state operates three television stations as well as national and regional radio stations. There are 117 private TV channels and 736 FM radio stations licensed for operation, at least 314 of which are community radio stations.[150] According to the 2011 census, the percentage of households possessing radios was 50.82%, televisions 36.45%, cable TV 19.33%, and computers 7.28%.[201] According to the Press Council Nepal classification, as of 2017[update], of the 833 publications producing original content, ten national dailies and weeklies are rated A+ class.[202] In 2019, Reporters Without Borders ranked Nepal 106th in the world in terms of press freedom.[203]

Music

Nepal's music reflects its diverse cultural heritage, with genres including Tamang Selo, Dohori, and Adhunik Geet, featuring artists like Narayan Gopal and Aruna Lama. Classical music is supported by institutions such as Kalanidhi Indira Sangeet Mahavidyalaya, while Western genres like Rock and Hip-Hop are gaining popularity.

Regional music traditions include Newar Music, Maithili Music, Gurung Music with Rodhi and Ghatu, Kirat Music with Dhan Nach, Magar Music with Salaijo and Kauda, Sherpa Music, and Tharu Music. Additionally, Bhajan (devotional), Filmi Music, and Ghazal contribute to Nepal's rich musical landscape.

Fashion

Traditional Nepali dress has evolved over time. Historically, women wore the sari, often paired with a blouse or cholo, for formal occasions, while men wore the dhoti. Everyday wear included the fariya or gunyu. The dhoti has been largely replaced by the suruwal in many contexts.[204][205][206]

In recent years, the sari has become formal wear, with jeans gaining popularity among younger generations. Traditional dresses like Daura-Suruwal and Gunyu-Cholo were removed as national dress in 2011 to avoid favoritism.[207] In high-altitude areas, Tibetan influences are seen in Sherpa attire, including the chuba. Hindu women often wear gold and silver jewelry, while Tharu women can don up to six kilograms of silver.[208]

Cinema

Nepali Cinema, or "Nepali Chalachitra," covers films in Nepali and Maithili languages. It began with Satya Harishchandra, the first Nepali-language film, released in 1951.[209] Aama was the first film produced in Nepal, and the Royal Nepal Film Corporation was established in 1971.[210] The 1980s marked a golden era with increased production and popularity. The industry declined during the Nepalese Civil War but began recovering around 2006 with digital films.[211]

Cuisine

Nepali cuisine features a rich variety of regional dishes, influenced by diverse ethnic groups and local ingredients. Key staples include rice, dhindo (a corn or millet porridge), and a range of vegetables and spices.[212] The Columbian Exchange introduced new staples like potatoes, tomatoes, and chili peppers to South Asia, which are now integral to Nepali cooking.[213]

A typical Nepali meal often comes as a thali, featuring a central portion of rice or dhindo, complemented by spiced lentils and vegetables. Traditional Nepali cuisine blends various spices like ginger, garlic, and turmeric.[214] Vegetarianism is common among Hindu and Buddhist communities due to religious beliefs, although the overall vegetarian population is lower compared to neighboring India.[215]

Regional cuisines add distinctive flavors, with momo dumplings and Newar cuisine like Samay baji being notable examples. Thakali cuisine, which blends Tibetan and Indian influences, is also well-regarded.[216][217] Sweet treats such as sel roti and kheer, and traditional drinks like raksi and chhaang, are also enjoyed across the country.[218]

Sports

Nepal has a rich sports culture with indigenous games like dandi biyo and kabaddi historically recognized as national sports until volleyball was officially declared the national sport in 2017.[190] While dandi biyo remains popular, its standardization has not been achieved, and kabaddi is still developing as a professional sport.[219]

Football and cricket are the most popular professional sports, with the national football team competing in regional tournaments and the cricket team gaining recognition as an associate member of the International Cricket Council.[220] Cricket has seen a rise in popularity, especially after Nepal's participation in the ICC World Twenty20.[221]

Nepal is also known for traditional sports like archery, which holds cultural significance.[222] Despite these achievements, sports infrastructure remains underdeveloped, hindering the ability to host international events and affecting overall growth in the sports sector.[223]

See also

Citations

Notes

- ^ English: /nɪˈpɔːl/,[15] /-ˈpɑːl/ nih-PAWL, -PAHL; Nepali: नेपाल [nepal]

- ^ Nepali: संघीय लोकतान्त्रिक गणतन्त्र नेपाल

- ^ According to the 2019 IUCN red list, two species of mammals, one bird species and three amphibian species are endemic to Nepal.[75]

- ^ Same-sex marriage with foreign nationals is recognized for visa eligibility as per a 2017 Supreme Court verdict.[105]

- ^ October 2019, IMF update, excludes Somalia and Syria.

- ^ October 2019, IMF update; excludes Somalia, Syria, and Venezuela.

References

- ^ "Nepal | Facts, History & News". www.infoplease.com. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ "Nepal | Culture, History, & People". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ "Indigenous Languages of Nepal: A Study of Prevention Barriers and Preservation Strategies". ResearchGate. Retrieved 3 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f "नेपालको संविधान २०७२" [Constitution of Nepal 2015] (PDF). 20 September 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 16 July 2019 – via Nepal Law Commission.

- ^ Mandal, Bidhi; Nayak, Ravi (9 June 2019). "Why English?". Republica. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ National Statistics Office (2021). National Population and Housing Census 2021, Caste/Ethnicity Report. Government of Nepal (Report). Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 October 2023. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ "Number of castes, ethnicities in Nepal increases to 142". The Kathmandu Post. 3 June 2023. Archived from the original on 12 July 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Subba, Sanghamitra (20 December 2019). "A future written in the stars". Nepali Times. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ The Sugauli Treaty of 1816 rendered moot the degree of independence of Nepal. The sixth point of the treaty directly questions the degree of independence of Nepal. The fact that any differences between Nepal and Sikkim will be "referred to the arbitration of the East India Company" sees Nepal as a semi-independent or a vassal state or tributary of the British empire.

- ^ Formal recognition of Nepal as an independent and sovereign state by Great Britain.

- ^ "Nepal". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 24 September 2022. (Archived 2022 edition.)

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (Nepal)". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. 10 October 2023. Archived from the original on 31 October 2023. Retrieved 14 October 2023.

- ^ "Gini Index (World Bank Estimate) – Nepal". World Bank. Archived from the original on 8 June 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2019". United Nations Development Programme. 2019. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 May 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ "Nepal | Definition of Nepal by Oxford Dictionary on Lexico.com also meaning of Nepal". Lexico Dictionaries | English. Archived from the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ^ Singh, Upinder (2008). A history of ancient and early medieval India: from the Stone Age to the 12th century. New Delhi: Pearson Longman. p. 477. ISBN 9788131716779.

- ^ Michaels, Axel (2024). Nepal: A History from the Earliest Times to the Present. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-197-65093-6.

- ^ Nanda R. Shrestha (1917). Historical Dictionary of Nepal. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 19. ISBN 9781442277700.

- ^ Hasrat, Bikram Jit (1970). History of Nepal: As told by its own and contemporary chroniclers. Hoshiarpur. p. 7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Malla, Kamal P. (1983). Nepāla: Archaeology of the Word (PDF). 3rd PATA International Tourism & Heritage Conservation Conference (1–4 November). The Nepal Heritage Society Souvenir for PATA Conference. Kathmandu. pp. 33–39. Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ For example, William Kirkpatrick, who visited Nepal in 1793, dismissed it as folklore, and Francis Buchanan-Hamilton agreed. Kirkpatrick, Col. William (1811). An Account of the Kingdom of Nepaul. New Delhi: Manjusri Publishing House. p. 169.; Hamilton (Buchanan), Francis (1819). An Account of the Kingdom of Nepal. Edinburgh: Archibald Constable & Co. p. 187.

- ^ Lassen, Christian (1847–1861). Indische Alterthumskunde [Indian Archaeology]. Bonn, H.B. Koenig.

- ^ Levi, Sylvain (1905). Le Nepal : Etude Historique d'Un Royaume Hindou. Vol. 1. pp. 222–223.

- ^ Chatterji, Suniti Kumar (1974). Kirata-Jana-Krti: The Indo-Mongoloids: Their Contribution to the History and Culture of India. The Asiatic Society. p. 64.

- ^ Klostermaier, Klaus K. (2007). A Survey of Hinduism: Second Edition. SUNY Press. p. 482. ISBN 978-1-4384-0933-7.

- ^ Landon, J. W. (1928). Nepal: Profile of a Himalayan Kingdom. Westview Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-89158-651-7.

- ^ Rose, Leo E. (1980). Nepal: Profile of a Himalayan Kingdom. Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-89158-651-7.

- ^ "Nepal Monarchy: Thakuri Dynasty". royalnepal.synthasite.com. Archived from the original on 30 December 2014. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ^ a b c Rose, Leo E.; Scholz, John T. (1980). Nepal: profile of a Himalayan kingdom. Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-89158-651-7.

- ^ Darnal, Prakash (31 December 2018). "A Review of Simarongarh's History on Its Nexus Areas with References of Archaeological Evidences". Dhaulagiri Journal of Sociology and Anthropology. 12: 18–26. doi:10.3126/dsaj.v12i0.22176. ISSN 1994-2672.

- ^ Chaudhary, Radhakrishna. Mithilak Itihas. ISBN 9789380538280.

- ^ Prinsep, James (March 1835). Prinsep, James (ed.). "The Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. Ed. By James Prinsep". The Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. 4 (39).

- ^ Petech, Luciano (1984). Medieval History of Nepal (PDF) (2nd ed.). Italy: Fondata Da Giuseppe Tucci. p. 125.

- ^ "Nepal - History".

- ^ "Nepal - History".

- ^ Father Giuseppe (1799). "Account of the Kingdom of Nepal". Asiatick Researches. Vernor and Hood. p. 308. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015.

- ^ Landon (1928). The Rise of Modern Nepal. pp. 68–69.

- ^ Landon (1928). The Rise of Modern Nepal. pp. 75–80.

- ^ Dietrich, Angela (1996). "Buddhist Monks and Rana Rulers: A History of Persecution". Buddhist Himalaya: A Journal of Nagarjuna Institute of Exact Methods. Archived from the original on 1 October 2013. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- ^ Lal, C.K. (16 February 2001). "The Rana resonance". Nepali Times. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- ^ "Facts About the 1951 Revolution: Nepal Democracy Day". Online Khabar. Retrieved 5 August 2024.

- ^ "Nepal's democracy: Revolutions and achievements and failures". The Kathmandu Post. Retrieved 5 August 2024.

- ^ Ramachandran, Shastri (2003). "Nepal as Seen from India". India International Centre Quarterly. 30 (2): 81–98. ISSN 0376-9771. JSTOR 23006108.

- ^ "First edition of The Rising Nepal published in 1965". Reddit. Retrieved 5 August 2024.

- ^ "The Fruits of Panchayat Development". HIMALAYA. Macalester College. Retrieved 6 August 2024.

- ^ "Nepalese force king to accept democratic reform, Jana Andolan (People's Movement), 1990". Global Nonviolent Action Database. Swarthmore College. Retrieved 6 August 2024.

- ^ "Nepal rejoices as peace deal ends civil war". The Guardian. 23 November 2006.

- ^ "Nepal palace shooting: King and nine others killed". CNN. 1 June 2001.

- ^ "King of Nepal seizes power". The Guardian. 2 February 2005.

- ^ Comprehensive Peace Agreement between the Government of Nepal and the CPN (Maoist) (PDF) (Report). United Nations Peacemaker. 22 November 2006.

- ^ "Nepal votes to end monarchy - CNN.com". CNN. 28 December 2007. Retrieved 6 August 2024.

- ^ "Why is Nepal's new constitution controversial?". BBC News. 16 September 2015.

- ^ "Nepal earthquake: Eight million people affected, UN says". BBC News. 29 April 2015.

- ^ "Nepal blockade: First vehicles pass through". BBC News. 4 February 2016. Retrieved 6 August 2024.

- ^ Ali, J. R.; Aitchison, J. C. (2005). "Greater India". Earth-Science Reviews. 72 (3–4): 170–173. Bibcode:2005ESRv...72..169A. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2005.07.005. ISSN 0012-8252.

- ^ Whelpton, John (2005). A History of Nepal. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80470-7.

- ^ "National Earthquake Monitoring & Research Center". Nepal Department of Mines and Geology. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Summerfield & Hulton, 1994;[incomplete short citation] Hay, 1998.[incomplete short citation]

- ^ Uddin, Kabir; Shrestha, Him Lal; Murthy, M. S. R.; Bajracharya, Birendra; Shrestha, Basanta; Gilani, Hammad; Pradhan, Sudip; Dangol, Bikash (15 January 2015). "Development of 2010 national land cover database for the Nepal". Journal of Environmental Management. Land Cover/Land Use Change (LC/LUC) and Environmental Impacts in South Asia. 148: 82–90. Bibcode:2015JEnvM.148...82U. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.07.047. PMID 25181944.

- ^ a b c "The Status of Nepal's Mammals: The National Red List Series". WWF Nepal. Archived from the original on 19 September 2020. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Paudel, Prakash Kumar; Bhattarai, Bishnu Prasad; Kindlmann, Pavel (2012), "An Overview of the Biodiversity in Nepal", Himalayan Biodiversity in the Changing World, pp. 1–40, doi:10.1007/978-94-007-1802-9_1, ISBN 978-94-007-1801-2

- ^ O'Neill, A. R.; Badola, H.K.; Dhyani, P. P.; Rana, S. K. (2017). "Integrating ethnobiological knowledge into biodiversity conservation in the Eastern Himalayas". Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 13 (1): 21. doi:10.1186/s13002-017-0148-9. PMC 5372287. PMID 28356115.

- ^ Jha, Sasinath (2008). "Status and Conservation of Lowland Terai Wetlands in Nepal". Our Nature. 6 (1): 67–77. doi:10.3126/on.v6i1.1657. ISSN 2091-2781.

- ^ "Forest cover has increased in Nepal of late". The Himalayan Times. 13 May 2016. Archived from the original on 24 August 2019. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- ^ Grantham, H. S.; et al. (2020). "Anthropogenic modification of forests means only 40% of remaining forests have high ecosystem integrity – Supplementary Material". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 5978. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.5978G. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19493-3. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7723057. PMID 33293507.

- ^ Stainton, J. D. A. (1972). Forests of Nepal. Hafner Publishing Company. ISBN 9780028527000. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ Goyal, Anupam (2006). The WTO and International Environmental Law: Towards Conciliation. Oxford University Press. p. 295. ISBN 978-0-19-567710-2. Archived from the original on 29 March 2024. Retrieved 26 August 2019. Quote: "The Indian government successfully argued that the medicinal neem tree is part of traditional Indian knowledge. (page 295)"

- ^ Hughes, Julie E. (2013). Animal Kingdoms. Harvard University Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-674-07480-4.

At same time, the leafy pipal trees and comparative abundance that marked the Mewari landscape fostered refinements unattainable in other lands.

- ^ Ameri, Marta; Costello, Sarah Kielt; Jamison, Gregg; Scott, Sarah Jarmer (2018). Seals and Sealing in the Ancient World: Case Studies from the Near East, Egypt, the Aegean, and South Asia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 156–7. ISBN 978-1-108-17351-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Quote: "The last of the centaurs has the long, wavy, horizontal horns of a markhor, a human face, a heavy-set body that appears bovine, and a goat tail ... This figure is often depicted by itself, but it is also consistently represented in scenes that seem to reflect the adoration of a figure in a pipal tree or arbor and which may be termed ritual. These include fully detailed scenes like that visible in the large 'divine adoration' seal from Mohenjo-daro." - ^ Paul Gwynne (2011). World Religions in Practice: A Comparative Introduction. John Wiley & Sons. p. 358. ISBN 978-1-4443-6005-9.

The tree under which Sakyamuni became the Buddha is a peepal tree (Ficus religiosa)

- ^ "National bird on verge of disappearance". The Himalayan Times. 16 April 2016. Archived from the original on 26 August 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ a b Sun, Hang (2002). "Tethys retreat and Himalayas-Hengduanshan Mountains uplift and their significance on the origin and development of the sino-himalayan elements and alpine flora". Acta Botanica Yunnanica. 24 (3): 273–288. ISSN 0253-2700. Archived from the original on 26 August 2019. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ^ USGS (5 May 1999). "The Himalayas: Two continents collide". Archived from the original on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ^ Karanth, K. P. (25 March 2006). "Out-of-India Gondwanan Origin of Some Tropical Asian Biota" (PDF). Current Science. 90 (6): 789–792. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ IUCN. "Table 8a: Total endemic and threatened endemic species in each country (totals by taxonomic group): VERTEBRATES" (PDF). IUCN Red List version 2019–21. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 August 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ "Table 5: Threatened species in each country (totals by taxonomic group)" (PDF). IUCN Red List version 2019-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 August 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ IUCN Nepal. "Red List of Mammal Species of Nepal". Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation, Nepal. "Bengal Florican Conservation Action Plan". Archived from the original on 19 August 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ "Conservation of white-rumped vultures in progress in Nepal". The Himalayan Times. 16 March 2018. Archived from the original on 26 August 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ "Mahottari declared 58th diclofenac-free district". The Himalayan Times. 8 August 2017. Archived from the original on 26 August 2019. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ^ "The Terai Arc Landscape Project (TAL) – Gharial Breeding Centre". WWF Nepal. Archived from the original on 26 August 2019. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ^ "'Joint Patrol' for wildlife conservation in CNP". The Himalayan Times. 22 March 2018. Archived from the original on 26 August 2019. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ^ "Nepal celebrates 'zero poaching year' for rhino, tiger and elephant". IUCN. 14 March 2014. Archived from the original on 22 November 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ^ Nepalnature.com (Organization); International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, Nepal; Nepal Ministry of Environment, Science, and Technology (1 October 2007). "Protected Areas of Nepal". Nepal biodiversity resource book: Protected areas, Ramsar sites, and World Heritage sites. International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development. p. 41. ISBN 9789291150335. Archived from the original on 18 August 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Nepal". Ramsar. Archived from the original on 8 July 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ "Nepal's holy Bagmati River choked with black sewage, trash". Associated Press. 17 August 2022. Archived from the original on 12 July 2023. Retrieved 8 May 2024.

- ^ "One more report ranks Nepal among most polluted countries in the world". Archived from the original on 8 July 2023. Retrieved 8 May 2024.

- ^ "WHO: Kathmandu, Nepal". Archived from the original on 9 July 2023. Retrieved 8 May 2024.

- ^ "Averting an air pollution disaster in South Asia". 21 April 2023. Archived from the original on 23 November 2023. Retrieved 8 May 2024.

- ^ "Trash and Overcrowding at the Top of the World". Archived from the original on 25 April 2024. Retrieved 8 May 2024.

- ^ "The very air we breathe | UNICEF Nepal". Archived from the original on 8 July 2023. Retrieved 8 May 2024.

- ^ "Air pollution takes its toll on Nepal's tourism capital". Archived from the original on 8 May 2024. Retrieved 8 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Nepal elections explained". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 14 August 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- ^ "Nepal 2015 Constitution - Constitute". www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ "प्रतिनिधिसभामा १२ दल, राष्ट्रिय पार्टी ७ मात्रै". ekantipur.com (in Nepali). Archived from the original on 13 August 2023. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- ^ "Is Nepal headed towards a communist state?". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 26 July 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- ^ Khadka, Narayan (1993). "Democracy and Development in Nepal: Prospects and Challenges". Pacific Affairs. 66 (1): 44–71. doi:10.2307/2760015. ISSN 0030-851X. JSTOR 2760015.

- ^ Kaphle, Anup (7 July 2010). "Long stalemate after Maoist victory disrupts life in Nepal". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 4 November 2016. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ^ "NCP to announce party department chiefs today". The Himalayan Times. 21 July 2019. Archived from the original on 18 August 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ "Ex-Maoist rebel leader Prachanda becomes Nepal PM for third time". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ^ "CA approves ceremonial prez, bicameral legislature". The Kathmandu Post. 16 September 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Australian Government-The Asia Foundation Partnership on Subnational Governance in Nepal. "Diagnostic Study of Local Governance in Federal Nepal 2017" (PDF). The Asia Foundation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 July 2019. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- ^ "Govt registers amendment bill to review 56 laws in bulk". Republica. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "International Views on the Death Penalty". Death Penalty Focus. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- ^ "निर्णय नं. ९९२१ – उत्प्रेषण/ परमादेश". Government of Nepal. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Newman, Graeme (2010). Crime and Punishment around the World. ABC-CLIO. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-313-35134-1.

- ^ "NEPAL: Corruption in Nepal – Curse or Crime?". Asian Human Rights Commission. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Crime rate in Nepal rose by 40 percent in past five fiscal years". Kathmandu Post. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Global Peace Index 2019". Vision of Humanity. Institute for Economics & Peace. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Nepali passport remains among world's weakest". kathmandupost.com. 12 January 2024. Retrieved 14 June 2024.

- ^ "Bilateral Relations – Ministry of Foreign Affairs Nepal MOFA". Retrieved 15 September 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Embassy of Nepal – Ministry of Foreign Affairs Nepal MOFA". Retrieved 15 September 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Nepalese Peacekeepers receive UN Medal". Retrieved 15 September 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Reviewing The Treaty Of 1950". Retrieved 11 September 2019.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Tibet's Road Ahead: Tibetans lose a haven in Nepal under Chinese pressure". Retrieved 12 September 2019.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Nepal, Bangladesh Can Become Better Trade Partners". Retrieved 12 September 2019.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Marking the diplomatic ties between Nepal and Israel". Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ Khadka, Narayan (1997). "Foreign Aid to Nepal: Donor Motivations in the Post-Cold War Period". Asian Survey. 37 (11): 1044–1061. doi:10.2307/2645740.

- ^ "Military expenditure (current USD) | Data". World Bank. Archived from the original on 13 August 2023. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- ^ "Military expenditure (% of GDP) | Data". World Bank. Archived from the original on 13 August 2023. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- ^ a b Raghavan, V. R. (2013). Nepal as a Federal State: Lessons from Indian Experience. Vij Books India. ISBN 9789382652014.

- ^ "New chief faces daunting task rebuilding Nepal Army's image". The Kathmandu Post. Archived from the original on 13 August 2023. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- ^ "Thapa to take charge of Nepali Army as acting CoAS". The Himalayan Times. 9 August 2018. Archived from the original on 17 September 2018. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- ^ "South Asia :: Nepal – The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency". Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- ^ "Nepali Army launches new helicopters". The Himalayan Times. 23 June 2015. Archived from the original on 23 July 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- ^ Adhikari, Indra (2015). Military and Democracy in Nepal. Routledge. ISBN 9781317589068.

- ^ "Army to rescue". Republica. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- ^ "Dolpa HQ connected to national road network". The Himalayan Times. 18 November 2018. Archived from the original on 14 August 2023. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ Pariyar, Kamal. "Women promoted to major for first time in NA infantry". Republica. Archived from the original on 1 June 2018. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- ^ "Bhakti Shah – the fight for gay and transgender rights in Nepal". Saferworld. Archived from the original on 13 August 2023. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- ^ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". IMF. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". IMF. Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ "The World Factbook: Nepal". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ a b "Nepal tourism generated Rs 240b and supported 1m jobs last year: Report". Kathmandu Post. Archived from the original on 30 July 2019. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ^ "Nepal has enough opportunities to tap tourists who visit other South Asian nations". The Himalayan Times. 6 November 2016. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ^ "The Issues with Overtourism in Destinations Like Mount Everest". Pegasus Magazine. Retrieved 8 June 2024.

- ^ "Nepal's Discovery of Tourism and the End of the Hippie Era". Retrieved 8 June 2024.

- ^ Sunuwar, Muna. "Homestay registration on the rise". Retrieved 2 December 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Everest: too many people, too much tourism". The Guardian. 27 June 2019. Retrieved 8 June 2024.

- ^ "Nepal's unemployment rate estimated at 11.4 percent". Kathmandu Post. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Tavernise, Sabrina (1 September 2004). "12 Hostages From Nepal Are Executed in Iraq". Retrieved 2 December 2019.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Basic minimum wage eludes Nepali migrant workers". The Himalayan Times. 9 May 2019. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Nepal receiving two dead migrant workers every day for past seven years". The Himalayan Times. 24 August 2018. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Nepalese Labor Migration—A Status Report". The Asia Foundation. 6 June 2018. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d Nepal energy sector assessment, strategy, and road map (PDF) (Report). ADB. March 2017. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Rai, Om Astha (2 November 2018). "From a fossil past to an electric future". Retrieved 3 December 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "More than half of Nepal's electricity imported from India". Nepali Times. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Energy sector in Nepal". Retrieved 15 July 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c Nepal Telecommunications Authority MIS Report Shrawan, 2076 (PDF) (Report). Nepal Telecommunications Authority. August 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d "South Asia :: Nepal – The World Factbook". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "The rise and fall of Nepal Airlines". Kathmandu Post. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Best and worst Asian countries for road quality". 22 February 2018.

- ^ "Population situation analysis of Nepal" (PDF). UNFPA. 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 November 2022. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20220206104652/https://cbs.gov.np/wp-content/upLoads/2022/01/Final%20Preliminary%20Report%20of%20Census%202021%20Newfinal.pdf

- ^ National Statistics Office (2021). National Population and Housing Census 2021, Caste/Ethnicity Report. Government of Nepal (Report).

- ^ "The Constitution of Nepal" (PDF). Nepal Gazette. 20 September 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ "Constitution of Napal (in Nepali)" (PDF). mohp.gov.np/. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ National Statistics Office (2024). National Population and Housing Census 2021: Population Composition of Nepal (PDF). National Statistics Office, Nepal. p. 52. Retrieved 18 May 2024.

- ^ Education in figures 2017 (PDF) (Report). Ministry of Education, Nepal. 2017. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Human Development Report 2010 – Nepal". Hdrstats.undp.org.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Nepal". UNESCO. 27 November 2016. Archived from the original on 24 February 2024. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ "Community-based School Management The Role Politics Plays". The Rising Nepal. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Free education to cost threefold". Kathmandu Post. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Types of scholarships provided to Nepalese students". Edusanjal. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Sharma, Nirjana (3 July 2015). "More students seeking 'no objection' to study abroad". Republica. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "The World Factbook". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Nepal Burden of Disease 2017 (PDF) (Report). NHRC, MoHP. 2019. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Nutrition". UNICEF. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Awale, Sonia (6 November 2019). "Nearly half of Nepali children still malnourished". Retrieved 4 December 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Maternal mortality reduction target hard to meet for Nepal". Kathmandu Post. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Health insurance plan yet to cover 38 districts in Nepal". Kathmandu Post. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "USDA, WFP to provide school meals". The Himalayan Times. 4 February 2018. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Envisioning a high-quality health system in Nepal". Retrieved 4 December 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Nepal". United Nations High Commission for Refugees. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ "A State Within a State: Tibetans in Nepal". The Diplomat. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ "UNHCR | Nepal: Bhutanese refugees find new life beyond the camps". 8 October 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ "Nepal | Global Focus". UNHCR. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ "Bleak outlook for Nepal's urban refugees". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ "नेपालमा अमेरिकादेखि उत्तरकोरियासम्मका कामदार". Online Khabar. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ "Population of Overseas Indians" (PDF). Ministry of External Affairs (India). 31 December 2018. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ Bista, Dor Bahadur (1991). Fatalism and Development: Nepal's Struggle for Modernization. Orient Blackswan. p. 44. ISBN 978-81-250-0188-1.

- ^ Acharya, Bala Ram (2005). "Sociological Analysis of Divorce: A Case Study from Pokhara, Nepal". Dhaulagiri Journal of Sociology and Anthropology. 1: 129–145. doi:10.3126/dsaj.v1i0.284. ISSN 1994-2672. Archived from the original on 13 August 2023. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ "Child Marriage". UNFPA Nepal. 30 December 2015. Archived from the original on 30 August 2023. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ "World's 'largest animal sacrifice' begins in defiance of ban". The Independent. 3 December 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2021.

- ^ Criveller, Gianni. "NEPAL Buddhists and animal rights activists against animal slaughter for Durga - Asia News". Asianews.it. Archived from the original on 16 January 2016. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- ^ Fernandez, Diana; Thapa, Kirti (8 August 2012). "Legislating Against Witchcraft Accusations in Nepal". The Asia Foundation. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ^ "Witch hunting". The Women's Foundation Nepal. 2019. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ^ "Cow becomes national animal of Nepal". The Times of India. 21 September 2015. Retrieved 3 April 2020.