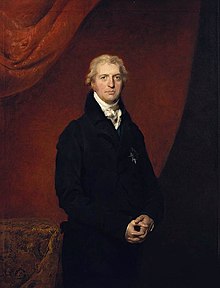

Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool

This article may incorporate text from a large language model. (August 2024) |

The Earl of Liverpool | |

|---|---|

| |

| Prime Minister of the United Kingdom | |

| In office 8 June 1812 – 9 April 1827 | |

| Monarchs | |

| Regent | George, Prince Regent (1812–1820) |

| Preceded by | Spencer Perceval |

| Succeeded by | George Canning |

| Secretary of State for War and the Colonies | |

| In office 1 November 1809 – 11 June 1812 | |

| Prime Minister | Spencer Perceval |

| Preceded by | The Viscount Castlereagh |

| Succeeded by | The Earl Bathurst |

| Leader of the House of Lords | |

| In office 25 March 1807 – 9 April 1827 | |

| Prime Minister |

|

| Preceded by | The Lord Grenville |

| Succeeded by | The Viscount Goderich |

| In office 17 August 1803 – 5 February 1806 | |

| Prime Minister | |

| Preceded by | The Lord Pelham |

| Succeeded by | The Lord Grenville |

| Home Secretary | |

| In office 25 March 1807 – 1 November 1809 | |

| Prime Minister | The Duke of Portland |

| Preceded by | The Earl Spencer |

| Succeeded by | Richard Ryder |

| In office 12 May 1804 – 5 February 1806 | |

| Prime Minister | William Pitt the Younger |

| Preceded by | Charles Philip Yorke |

| Succeeded by | The Earl Spencer |

| Foreign Secretary | |

| In office 20 February 1801 – 14 May 1804 | |

| Prime Minister | Henry Addington |

| Preceded by | The Lord Grenville |

| Succeeded by | The Lord Harrowby |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Robert Banks Jenkinson 7 June 1770 London, England |

| Died | 4 December 1828 (aged 58) Kingston upon Thames, Surrey, England |

| Resting place | Hawkesbury Parish Church, Gloucestershire, England |

| Political party | Tory |

| Spouses | |

| Parent | Charles Jenkinson (father) |

| Education | Charterhouse School |

| Alma mater | Christ Church, Oxford |

| Signature | |

Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool, KG, PC, FRS (7 June 1770 – 4 December 1828) was a British Tory statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1812 to 1827. He also held many other important cabinet offices such as Foreign Secretary, Home Secretary and Secretary of State for War and the Colonies. He was also a member of the House of Lords and served as leader.

After becoming Prime Minister in 1812, Liverpool intensified efforts against Napoleon Bonaparte by providing subsidies to the allies until the coalition victory at Leipzig 1813. Despite these achievements, the country financially struggled with constant requests for Treasury bill roll overs from the Bank of England and heavy taxation. However, in June 1815, Napoleon was defeated for the final time at the Battle of Waterloo by Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, ending the Napoleonic Wars. Liverpool outlined a peace settlement after the war at the Congress of Vienna which imposed no reparations and left France with most of her colonies, and secured no additional gains for Britain.[1]

As prime minister, Jenkinson called for repressive measures at domestic level to maintain order after the Peterloo Massacre of 1819. He dealt smoothly with the Prince Regent when King George III was incapacitated. He also steered the country through the period of radicalism and unrest that followed the Napoleonic Wars. He favoured commercial and manufacturing interests as well as the landed interest. He sought a compromise of the heated issue of Catholic emancipation. The revival of the economy strengthened his political position. By the 1820s, he was the leader of a reform faction of "Liberal Tories" who lowered the tariff, abolished the death penalty for many offences, and reformed the criminal law. By the time of his death, however, the Tory party, which had dominated the House of Commons for over 40 years, was ripping itself apart. Under his leadership, the Tory Party was able to survive the major calamities of the period without major impact.[2]

Important events during his tenure as prime minister included the War of 1812 with the United States, the Sixth and Seventh Coalitions against the French Empire, the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars at the Congress of Vienna, the Corn Laws, the Peterloo Massacre against pro-democracy protestors, the Trinitarian Act 1812 and the emerging issue of Catholic emancipation.[3] Despite being called "the Arch-mediocrity" by a later Conservative prime minister, Benjamin Disraeli, scholars rank him highly among all British prime ministers.[4] He is the third longest serving prime minister in British history, with an unbroken 14-year tenure surpassed only by those of Robert Walpole and William Pitt the Younger.[5]

Early life

[edit]Jenkinson was baptised on 29 June 1770 at St. Margaret's, Westminster, the son of George III's close adviser Charles Jenkinson, later the first Earl of Liverpool, and his first wife, Amelia Watts. Jenkinson's 19-year-old mother, who was the daughter of a senior East India Company official, William Watts, and of his wife Begum Johnson, died from the effects of childbirth one month after his birth.[6]

The Jenkinsons were members of the landed gentry and were descendants of the explorer and merchant Anthony Jenkinson who led four diplomatic missions to Russia between 1558 and 1571.[7][8] With this fame and fortune, the Jenkinsons established themselves as country squires in Oxfordshire and gradually rose through the social order when they were given a baronetcy during the Restoration era. The first four baronets, including Liverpool's great-grandfather and two great uncles, all served as members of parliament for Oxfordshire as High Tories from 1661 until 1727 when they lost their parliamentary seat in the Whig landslide during that year’s general election.[9] The family were committed supporters of conservative politics and high-church Anglicanism adhered to the maintenance of tradition. Despite occasional departures from Tory party values, Jenkinsons’ deference to the monarch and support for the Church of England consistently aligned them with the Tories. His mother’s family had a prominent colonial presence in India.[10] Through his mother's grandmother, Isabella Beizor, Jenkinson was descended from Portuguese settlers in India; he may also have been one-sixteenth Indian in ancestry.[11][12][13]

Jenkinson first received his education at a preparatory school at Parsons Green in Fulham until at the age of 12, Jenkinson was educated at Charterhouse School of which the education was considered broader than that of Eton College.[14] He spent 1/2 years at Charterhouse, which seemed to have been unremarkable. A letter from his father in November 1784, indicated he displayed signs of talent uncharacteristic of him, writing that 'the principal happiness I shall expect to enjoy in the decline of life is that which I shall derive from your prosperity and eminence.'[15] In 1786, he was later matriculated at Christ Church, Oxford, in 1787.[16][17] While at Oxford, Liverpool engaged in the traditional “Grand Tour,” which took him to Paris in July 1789 where he witnessed the storming of the Bastille. Liverpool described the event where the mob beheaded the garrison’s governor and triumphantly paraded with his severed head as “one of the most extraordinary revolutions that ever has happened.”[18] In the summer of 1789, Jenkinson spent four months in Paris to perfect his French and enlarge his social experience. He returned to Oxford for three months to complete his terms of residence, and in May 1790 was created Master of Arts.[14]

Early career (1790–1812)

[edit]Member of Parliament

[edit]He won election to the House of Commons in 1790 for Rye, a seat he would hold until 1803; at the time, however, he was below the age of assent to Parliament, so he refrained from taking his seat and spent the following winter and early spring in an extended tour of Continental Europe. This tour took in the Netherlands and Italy; at its conclusion he was old enough to take his seat in Parliament. It is not clear exactly when he entered the Commons, but as his twenty-first birthday was not reached until almost the end of the 1791 session, it is possible that he waited until the following year. In his maiden speech, he supported Prime Minister William Pitt's attempt to persuade Parliament to support a vigorous response to Russian encroachments in the Black Sea during the Ochakov crisis.[19]

House of Commons

[edit]With the help of his father's influence, and his political talent, he rose relatively quickly in the Tory government. In February 1792 he gave the reply to Samuel Whitbread's critical motion on the government's Russian policy. He delivered several other speeches during the session and was a strong opponent of abolitionism and William Wilberforce. He served as a member of the Board of Control for India from 1793 to 1796.

In the defence movement that followed the outbreak of hostilities with France, Jenkinson was one of the first of the ministers of the government to enlist in the militia. He became a colonel in the Cinque Ports Fencibles in 1794, his military duties leading to frequent absences from the Commons. His regiment was sent to Scotland in 1796 and he was quartered for a time in Dumfries.

In 1797 the then Lord Hawkesbury was the cavalry commander of the Cinque Ports Light Dragoons who ran amok following a protest against the Militia Act at Tranent in East Lothian, twelve civilians being killed. Author James Miller wrote in 1844 that "His lordship was blamed for remaining at Haddington, as his presence might have prevented the outrages of the soldiery."[20]

His parliamentary attendance also suffered from his reaction when his father angrily opposed his projected marriage with Lady Louisa Hervey, daughter of the Earl of Bristol. After Pitt and the King had intervened on his behalf the wedding finally took place at Wimbledon on 25 March 1795. In May 1796, when his father was created Earl of Liverpool, he took the courtesy title of Lord Hawkesbury and remained in the Commons. He became Baron Hawkesbury in his own right and was elevated to the House of Lords in November 1803 in recognition for his work as Foreign Secretary.[citation needed] He also served as Master of the Mint (1799–1801).[16]

Foreign Secretary (1801–1804)

[edit]This section is in a state of significant expansion or restructuring. You are welcome to assist in its construction by editing it as well. This template was placed by @Altonydean. If this section has not been edited in several days, please remove this template. If you are the editor who added this template and you are actively editing, please be sure to replace this template with {{in use}} during the active editing session. Click on the link for template parameters to use.

This article was last edited by Neveselbert (talk | contribs) 7 seconds ago. (Update timer) |

In Henry Addington's government, he entered the cabinet in 1801 as Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, in which capacity he negotiated the Treaty of Amiens with France.[21] Most of his time as Foreign Secretary was spent dealing with the nations of France and the United States.

Early negotiations were primarily handled by James Harris, 1st Earl of Malmesbury and later Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis. However, it was Hawkesbury who took responsibility for formulating the requirements and gaining Cabinet approval for them, acknowledging that the military situation did not favour Britain’s war objectives set at the outset of the conflict. In early February, Napoleon made peace with Austria at Lunéville, which solidified French dominance on the continent, and by the time negotiations began, Britain only aimed to ensure France's evacuation of Egypt. News of General Abercrombie's victory at Alexandria further weakened French influence in the region. However, negotiations were complicated by Napoleon's annexation of territories in Italy and his pressure on Britain regarding Malta.[22]

By March, the preliminary Treaty of Amiens was signed in London, marking a temporary cessation of hostilities. Under the peace terms, Britain was to agree to give up its colonial gains made during the war, retaining only the Cape of Good Hope (later exchanged for Trinidad), Ceylon, and Cochin. Despite the less than favorable terms, the treaty was defended by Lord Hawkesbury in the House of Commons amidst growing pressure for a more favourable peace in Britain. The public celebrated the peace, though it was described by some, like Richard Brinsley Sheridan, as a peace "everyone was glad of but no one was proud of.[23]

The cause for celebrations were short-lived as reports of Napoleon's activities surfaced in the British press, leading to diplomatic tensions. French demands to banish émigrés from England and stalled negotiations to normalise trade relations further strained the fragile peace. Napoleon's subsequent annexations in Italy and his actions in Holland and Switzerland heightened British concerns. Attempts to secure stability through diplomatic channels, including offers by Charles Whitworth, 1st Earl Whitworth to recognise French gains in Italy in exchange for British occupation of Malta, failed to resolve tensions.[23]

In May 1803, Lord Whitworth left Paris, and Britain resumed hostilities, marking the end of the fourteen-month interlude of peace. The resumption of war was met with criticism in Parliament, where the government was faulted for its handling of negotiations and accused of premature disarmament. Despite initial support for Addington's government, dissent quickly grew and a year later Pitt was reappointed as Prime Minister.[24]

Home Secretary and Leader of the Lords (1804–1806; 1807–1809)

[edit]He continued to serve in the cabinet as Home Secretary in Pitt the Younger's second government. While Pitt was seriously ill, Liverpool was in charge of the cabinet and drew up the King's Speech for the official opening of Parliament. When William Pitt died in 1806, the King asked Liverpool to accept the post of Prime Minister, but he refused, as he believed he lacked a governing majority. He was then made leader of the Opposition during Lord Grenville's ministry (the only time that Liverpool did not hold government office between 1793 and after his retirement). In 1807, he resumed office as Home Secretary in the Duke of Portland's ministry.[16]

Hawkesbury's immediate duties as Home Secretary was to prepare the country for a potential invasion by Napoleon, which was regarded a possible event. He faced obstacles from the King, who wanted to personally lead the defense forces, and also from the George, Prince of Wales, who publicly complained about not being promoted beyond the rank of Colonel in the 10th Hussars. Fortunately, in the autumn of 1805, following the decisive victory at the Battle of Trafalgar, an invasion was cast as impossible without control of the English Channel and the Royal leadership was never put to the test.[25]

Hawkesbury also aimed to crackdown on the emerging issues of trade unions. Industrialists urged him to prosecute the unions as illegal combinations with him leaving the matter to the attorney general, Spencer Perceval, who confirmed the illegality of the unions' actions as they aimed to raise wages and impose a closed shop. However, Perceval moved against government prosecution, fearing it would worsen relations between employers and workers. During this time, Hawkesbury began addressing the issue of Catholic Emancipation, which had become a dominant issue in British politics in the early 19th Century. Opinions on this matter varied among the political lines, with some supporting the notion while facing considerable opposition, from including Hawkesbury, opposed it due to concerns about loyalty to the Protestant values of the country and the influence of his Evangelical wife, Louisa.[26]

War Secretary (1809–1812)

[edit]Lord Liverpool (as he had now become by the death of his father in December 1808) accepted the position of Secretary of State for War and the Colonies in Spencer Perceval's government in 1809. Liverpool's first step on taking up his new post was to elicit from General Arthur Wellesley (the future Duke of Wellington) a strong enough statement of his ability to resist a French attack to persuade the cabinet to commit themselves to the maintenance of his small force in Portugal. In 1810 Liverpool was made a colonel of militia.[27]

Liverpool's first action at the War Office was to withdraw the failed Walcheren Expedition that was at risk of being destroyed by the French after Austria’s defeat at Battle of Wagram. The fortifications, docks, and arsenal at the Scheldt’s Mouth were destroyed and the remaining troops were evacuated with the last regiment returning home by Christmas.[28]

Liverpool's major focus was on outgoing Peninsular War. In 1809,the Duke of Wellington captured the Portuguese city of Oporto and achieved victory at Talavera, but with France concentrating all efforts on Spain, a temporary retreat became necessary. Liverpool immediately contacted Wellington to assess the situation and Wellington expressed confidence in ultimate progress, despite anticipating a French invasion of Portugal. Liverpool became committed to the war and reinforcing Wellington's forces, ensuring 30,000 men would remain in the field. Throughout the year 1810, both Wellington and Liverpool were criticised by opposition, as the campaign in Portugal was seen as a costly sideshow. Despite growing concerns within the government and continued opposition in Parliament, Liverpool remained steadfast, vocally advocating for sustained but moderate efforts. He wrote to Wellington in September 1810, stating the need to choose between consistent exertion and a grand, short-term campaign that could not be sustained.[29]

Following Wellington's retreat to the Lines of Torres Vedras in the winter of 1810-11, it became increasingly evident that the Portuguese campaign was yielding positive results. Consequently, British troop numbers in Portugal were gradually increased to 50,000 by early 1811. Charles Grey, leader of the Whig opposition, acknowledged the success of army’s campaign.[30]

In contrast to these achievements, Liverpool's responsibilities for the colonies saw minimal conflict, with Canada being the only notable exception. French Canadians, unhappy with the Anglicised constitution established by the 1791 Canada Act, hoped for Bonaparte to overturn the Treaty of Paris. However, Liverpool supported upholding the 1791 Constitution, believing that any changes could provoke discontent and jeopardise not only Canada but also Ireland.[31]

In the House of Lords, Liverpool faced a crisis when George III's mental health deteriorated following the death of his daughter, Princess Amelia, in November 1810. Initial expectations were that his illness was temporary, but by the end of 1810, it became apparent that his condition have gone worse. In December, the ministry decided to establish a Regency with Liverpool proposing three Resolutions on December 27, stating that Parliament should address the suspension of monarchical authority and appoint a Regent with him arguing that the constitution deliberately lacked provisions for a Regency, allowing Parliament to arrange one as needed. Liverpool cited the precedent of Henry VI's minority when Parliament rejected the Duke of Gloucester's claim to act as Regent. This led to the swift passage of the 1811 Regency Bill, which appointed the Prince of Wales as Regent with certain restrictions for a year. The bill received Royal Assent on February 5, 1811.[32]

Prime Minister (1812–1827)

[edit]It has been suggested that portions of this section be split out into another article titled Premiership of Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool. (Discuss) (August 2024) |

The Liverpool government

[edit]For the most of key positions Liverpool appointed men of influence in both Houses of Parliament and of reasonable ability. These included Castlereagh (reappointed as Foreign Secretary), former Prime Minister Lord Sidmouth as Home Secretary, Lord Eldon as Lord Chancellor, and Lord Melville (son of Henry Dundas) as First Lord of the Admiralty. However, Liverpool had trouble with a new promotion to the position of Secretary of State for War and the Colonies which proved to be challenging to fill. The position was initially offered to William Wellesley-Pole (brother of the Marquess Wellesley and Wellington), who declined due to a lack of skill. After further consideration, Liverpool appointed the Earl Bathurst, though competent was a member of the ultra conservative faction of the party.[33] The greatest difficulty came with the an attempt to bring Canning to office, who refused out of animosity toward Castlereagh, with latter agreeing to leave the Commons in favour of Canning.[34]

Foreign affairs

[edit]Congress of Vienna

[edit]Liverpool first supported the idea of having Napoleon facing trial and execution as a rebel, but was convinced otherwise by Castlereagh and the Cabinet who sought confinement far from Europe with the former Emperor being exiled to the island of St. Helena in the South Atlantic.[35]

Domestic affairs

[edit]Royal scandal

[edit]Liverpool and the government faced serious crisis again in the ensuing marital dispute between King George IV and his wife Queen Caroline of Brunswick. The couple have been living apart since their separation in 1814 with the Queen leaving the country indefinitely to mainland Europe and the King therefore wanted the government pass legislation to divorce her. During the upcoming coronation for the King in June, 1820, Caroline returned to the country to take her place as queen consort. Earlier, the King cannot divorce Caroline unless on grounds of adultery and Liverpool was tasked with sending a investigation to Milan with investigators setting up the “Milan Commission” in 1818 with the aim of finding possible witnesses to testify against the Queen’s misconduct and her alleged affair with one of her servants, Bartolommeo Pergamum. Testimonies against Caroline selected from all possible witnesses, including her servants. However, the Government worried about a mass scandal and sought to mediate between George and Caroline into a long-term separation agreement which was superseded by the passing of King George III 29 January 1820. The King attempted to remove from the event by excluding her from the Church liturgy and instructed foreign embassies to deny recognition to her status as queen consort. When she returned to the country, the King sought a quick divorce and with the evidence provided by the Milan Commission being sent to the Houses of Parliament in sealed green bags with a House of Lords committee being appointed to examine the evidence. In the ensuing inquiry, the King and the Liverpool government introduced the “Pains and Penalties Bill” that was “to deprive Caroline of the rights and title Queen Consort and to dissolve her marriage to George” that led to a trial on 17 August to establish the accuracy of the preamble in determining “a most unbecoming and degrading Intimacy commenced between Bartolomeo Pergami and Her said Royal Highness”. The bill was passed in the House of Lords following its second hearing with a vote of 119-94. However, the majority support for the bill shrank and knowing that its passage in the House of Commons would be futile, Liverpool declared “I could not be ignorant of the state of public feeling with regard to this measure” and due to growing popular support for Caroline and widespread dislike of both the King and the government, the Bill was abandoned. [36]

Post-premiership (1827–1828)

[edit]Retirement

[edit]Jenkinson's first wife, Louisa, died at 54. He married again on 24 September 1822 to Mary Jenkinson, Countess of Liverpool.[37] Mary Chester was a close friend of the late countess. He was the first and only British Prime Minister to marry while in office until Boris Johnson in 2020.[38] Jenkinson finally retired on 9 April 1827 after suffering a severe cerebral hemorrhage at his Fife House residence in Whitehall two months earlier,[39] and asked the King to seek a successor.

Liverpool opted to reside near London, choosing Combe House, a country residence in Kingston upon Thames, Surrey. The house was an original Tudor structure until it was modified by a Georgian mansion later built by Sir John Soane, who also added a library. This house stood until 1933, when it was demolished and replaced by residential housing. He like many of his predecessors before him, did not preferred the architecture of the Gothic revival movement which served as the main alternative to the prevailing Classical architectural style, which was as a result of the legacy of the Protestant Reformation that rejected anything explicitly 'Catholic'.[40]

Death

[edit]He suffered another minor stroke in July, after which he lingered on at Coombe, Kingston upon Thames until a third attack on 4 December 1828 from which he died.[41] He had been in stable health since then and without any symptoms of a serious condition until on Friday in December at nine o' clock, he showed signs of spasms and convulsions with a dispatch to one of his medical attendants, Mr. Sandford. Before he could arrive, Liverpool was dead at ten o' clock with his half-brother Cecil Jenkinson and his wife Mary at his apartment.[42] Having died childless, he was succeeded as Earl of Liverpool by his younger half-brother Charles Jenkinson, 3rd Earl of Liverpool. Jenkinson was buried in Church of St Mary, Hawkesbury beside his father and his first wife.

Legacy

[edit]Assessment

[edit]Robert William Seton-Watson sums up Jenkinson's strengths and weaknesses:

No one would claim Liverpool as a man of genius, but he had qualities of tact, firmness and endurance to which historians have rarely done full justice: and thus it came about that he held the office of Premier over a period more than twice as long as any other successor of Pitt, long after peace had been restored to Europe. One reason for his ascendancy was that he had an unrivalled insight into the whole machinery of government, having filled successively every Secretaryship of State, and tested the efficiency and mutual relations of politicians and officials alike.... He had a much wider acquaintance with foreign affairs than many who have held his high office.[43]

John W. Derry says Jenkinson was:

[A] capable and intelligent statesman, whose skill in building up his party, leading the country to victory in the war against Napoleon, and laying the foundations for prosperity outweighed his unpopularity in the immediate post-Waterloo years.[44]

According to Norman Gash, Liverpool possessed two distinct traits: his staunch conservatism and his role as a capable administrator, both that contribute to his relatively minor position in historical accounts. As a conservative, Liverpool adhered rigidly to his principles for three decades, resisting pressures for reform and reaction alike. He maintained a firm stance on issues such as Catholic emancipation, parliamentary reform, economic and foreign policies, support for trade outdone by pragmatism. This likely led to his historical neglect and unfavourable reputation, particularly as his death marked the end of Tory dominance and ushered a period of rapid change and liberal leadership that overshadowed his legacy. The prevailing historical narrative, often written by reformist and liberal-minded individuals led to Liverpool's disdainful assessment.[45]

Although he resisted major reform and his pragmatic innovations may seem insignificant, his advocacy for free-market principles and reluctance to embrace protectionism may have indirectly influenced the 19th-century economic boom. Additionally, his aversion to adopting true party politics in Parliament might have had its merits. Despite his firm control over power, Liverpool's tenure as Prime Minister is viewed as one of mediocrity due to his lack of assertiveness in shaping events in contrast to figures like Wellington who were more reactionary. Ironically, the later Conservative (i.e Tory) Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli criticised Liverpool harshly, labelling him as "the arch mediocrity" which stemmed from Liverpool's failure to impose significant changes, despite achievements in foreign and economic policy.[45]

Liverpool and his government is widely regarded as one of the most reactionary and repressive in British history, led by conservative Tory principles that were derived from pre-French Revolution societal structures of which the government was deeply concerned. This resulted in policies that were designed to maintain the status quo which ignored the widespread problems of unemployment, economic stagnation and social unrest. Although acknowledging the dire situation of the country, the government became fixated on only signs of revolutionary insurrection one that did not solve the main issues of domestic unrest and struggled with the transition to a peacetime reconstruction in spite of rapid changes in the Industrial Revolution. As such, the rigid and short-term policies of his government failed to address the needs of post-war Britain, cementing its reputation one of the most reactionary in the history.[46]

In popular culture

[edit]Jenkinson was the first British prime minister to regularly wear long trousers instead of breeches. He was also the first prime minister to cut his hair short instead of wearing a wig or wearing long hair in a queue.[47] He entered office at the age of 42 years and one day, making him younger than all of his successors. Liverpool served as prime minister for a total of 14 years and 305 days, making him the longest-serving prime minister of the 19th century. As of 2023, none of Liverpool's successors has served longer. He is third only to William Pitt the Younger and Robert Walpole who each served longer tenures.[48]

In London, Liverpool Street and Liverpool Road, Islington, are named after Lord Liverpool. The Canadian town of Hawkesbury, Ontario, the Hawkesbury River and the Liverpool Plains, New South Wales, Australia, Liverpool, New South Wales, and the Liverpool River in the Northern Territory of Australia were also named after Lord Liverpool.[49]

Lord Liverpool, as Prime Minister to whose government Nathan Mayer Rothschild was a lender, was portrayed by American actor Gilbert Emery in the 1934 film The House of Rothschild.[50]Liverpool was also portrayed by André van Gyseghem in 1979 mini-series the Prince Regent and by Robert Wilfort in the 2018 film Peterloo .[51][52]

Lord Liverpool's ministry (1812–1827)

[edit]

- Lord Liverpool – First Lord of the Treasury and Leader of the House of Lords

- Lord Eldon – Lord Chancellor

- Lord Harrowby – Lord President of the Council

- Lord Westmorland – Lord Privy Seal

- Lord Sidmouth – Secretary of State for the Home Department

- Lord Castlereagh (Lord Londonderry after 1821) – Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs and Leader of the House of Commons

- Lord Bathurst – Secretary of State for War and the Colonies

- Lord Melville – First Lord of the Admiralty

- Nicholas Vansittart – Chancellor of the Exchequer

- Lord Mulgrave – Master-General of the Ordnance

- Lord Buckinghamshire – President of the Board of Control

- Charles Bathurst – Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

- Lord Camden – minister without portfolio

Changes

[edit]- Late 1812 – Lord Camden leaves the Cabinet

- September 1814 – William Wellesley-Pole (Lord Maryborough from 1821), the Master of the Mint, enters the Cabinet

- February 1816 – George Canning succeeds Lord Buckinghamshire at the Board of Control

- January 1818 – F. J. Robinson, the President of the Board of Trade, enters the Cabinet

- January 1819 – The Duke of Wellington succeeds Lord Mulgrave as Master-General of the Ordnance. Lord Mulgrave becomes minister without portfolio

- 1820 – Lord Mulgrave leaves the cabinet

- January 1821 – Charles Bathurst succeeds Canning as President of the Board of Control, remaining also at the Duchy of Lancaster

- January 1822 – Robert Peel succeeds Lord Sidmouth as Home Secretary

- February 1822 – Charles Williams-Wynn succeeds Charles Bathurst at the Board of Control. Bathurst remains at the Duchy of Lancaster and in the Cabinet

- September 1822 – Following the suicide of Lord Londonderry, George Canning becomes Foreign Secretary and Leader of the House of Commons

- January 1823 – Vansittart, elevated to the peerage as Lord Bexley, succeeds Charles Bathurst as Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. F. J. Robinson succeeds Vansittart as Chancellor of the Exchequer. He is succeeded at the Board of Trade by William Huskisson

- 1823 – Lord Maryborough, the Master of the Mint, leaves the Cabinet. His successor in the office is not a Cabinet member

Arms

[edit]

|

|

References

[edit]- ^ "Lord Liverpool". Historic UK. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ "BBC - h2g2 - Lord Liverpool - British Prime Minister". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 5 August 2024.

- ^ Gash, Norman (1984). Lord Liverpool : the life and political career of Robert Banks Jenkinson, Second Earl of Liverpool, 1770-1828 /. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-53910-5.

- ^ Paul Strangio; Paul 't Hart; James Walter (2013). Understanding Prime-Ministerial Performance: Comparative Perspectives. Oxford UP. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-19-966642-3.

- ^ "Lord Liverpool - our greatest Prime Minister?". Lord Lexden OBE. 26 January 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2024.

- ^ D. Leonard 2008 Nineteenth-Century British Premiers: Pitt to Rosebery. Palgrave Macmillan: p. 82.

- ^ "Lord Liverpool". Friends of St Mary's Hawkesbury. 15 August 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2024.

- ^ "Anthony Jenkinson". Government Art Collection. Retrieved 18 July 2024.

- ^ Hutchinson 2008, p. 1.

- ^ "Lord Liverpool, New Biography: Perceptive, Informative | National Review". National Review. 1 September 2018. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ Blake, Robert (18 October 1984). "Weathering the storm". London Review of Books. Vol. 6, no. 19. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ "Edward Croke's wife, Isabella Beizor (c. 1710–80), was a Portuguese Indian creole, thus giving Liverpool a trace (probably about one sixteenth, but maybe less) of Indian blood." Hutchinson, Martin, Britain's Greatest Prime Minister: Lord Liverpool

- ^ "It is true that [Lord Liverpool's] maternal grandmother was a Calcutta-born woman, Frances Croke ... there is no evidence that her half-Portuguese mother, Isabella Beizor, was Eurasian." Brendon, de Vyvyen, Children of the Raj

- ^ a b Hutchinson, Martin; Dowd, Kevin (14 October 2021). "The Economic Policies of Lord Liverpool".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Hutchinson 2008, p. 3.

- ^ a b c Chisholm 1911.

- ^ Foster, Joseph (1888–1892). . Alumni Oxonienses: the Members of the University of Oxford, 1715–1886. Oxford: Parker and Co – via Wikisource.

- ^ Sacramone, Anthony (23 October 2019). "Lord Liverpool's Antidote to Revolution". Intercollegiate Studies Institute. Retrieved 11 July 2024.

- ^ Simms, Brendan (13 May 2018). "An accidental prime minister: the underrated career of the pragmatic Lord Liverpool". New Statesman. Retrieved 18 July 2024.

- ^ Miller, James (1844). "Dreadful Riot and Military Massacre at Tranent, on the First Balloting for the Scots Militia for the County of Haddington". The Lamp of Lothian, or, The history of Haddington: in connection with the public affairs of East Lothian and of Scotland, from the earliest records to the present period. Haddington: James Allan – via Scottish Mining.

- ^ "Lord Liverpool". Victorian Web. 4 March 2002.

- ^ Robertson, p. 23-24.

- ^ a b Robertson, p. 24.

- ^ Robertson, p. 24-25.

- ^ Hutchinson 2008, p. 16.

- ^ Hutchinson 2008, p. 16-17.

- ^ JENKINSON, Hon. Robert Banks (1770–1828), of Coombe Wood, nr. Kingston, Surr. | History of Parliament Online "The History of Parliament" article by R. G. Thorne

- ^ Hutchinson 2008, p. 23.

- ^ Hutchinson 2008, p. 23-24.

- ^ Hutchinson 2008, p. 24.

- ^ Hutchinson 2008, p. 24-25.

- ^ Hutchinson 2008, p. 25-26.

- ^ Robertson, p. 40-41.

- ^ Hutchinson 2008, p. 28.

- ^ Davies, Huw (21 August 2024). "The Legacy of Waterloo: War and Politics in Europe in the Nineteenth Century". British Journal for Military History. 1 (1): Pages: 21 – via Academia.edu.

- ^ conniejeffery (16 June 2020). "The royal scandal that helped change British politics: the 1820 Queen Caroline affair". The History of Parliament. Retrieved 20 August 2024.

- ^ Gash, Norman (2004). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Volume 29. Oxford University Press. p. 988. ISBN 978-0-19-861379-4.

- ^ Bird, Steve (29 February 2020). "Boris Johnson: First British prime minister in nearly 200 years to marry while in office". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 30 July 2024.

- ^ "Robert Jenkinson, Lord Liverpool". Archived from the original on 30 March 2015. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- ^ Seat, Matthew Beckett-The Country (20 January 2011). "earl of liverpool". The Country Seat. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Edinburgh. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ^ "Death of Lord Liverpool: 4 December 1828". www.historyhome.co.uk. Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- ^ R. W. Seton-Watson, Britain in Europe (1789–1914): A Survey of Foreign Policy (1937) (1937), p. 29.

- ^ John Cannon, ed. (2009). The Oxford Companion to British History. p. 582.[ISBN missing]

- ^ a b "Napoleon Series Reviews: Lord Liverpool: The Life and Political Career of Robert Banks Jenkinson". www.napoleon-series.org. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ "Britain's Guardian Ganders – Wilcuma". Retrieved 10 August 2024.

- ^ Hutchinson, Martin. "Robert Banks Jenkinson, Second Earl of Liverpool". www.lordliverpool.com. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ "Longest Serving British Prime Ministers". WorldAtlas. 26 March 2019. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ "Place Names Register Extract – Liverpool River". NT Place Names Register. Northern Territory Government. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ^ The House of Rothschild (1934) - Alfred L. Werker, Sidney Lanfield | Cast and Crew | AllMovie. Retrieved 13 July 2024 – via www.allmovie.com.

- ^ "Peterloo (2018) Cast". www.cinema.com. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ "André van Gyseghem". watch.plex.tv. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Brock, W. R. (1943). Lord Liverpool and Liberal Toryism 1820 to 1827. CUP Archive. p. 2.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 804. This contains an assessment of his character and achievements.

- Cookson, J. E. Lord Liverpool's administration: the crucial years, 1815–1822 (1975)

- Gash, Norman. Lord Liverpool: The Life and Political Career of Robert Banks Jenkinson, Second Earl of Liverpool 1770–1828 (1984)

- Gash, Norman. "Jenkinson, Robert Banks, second earl of Liverpool (1770–1828)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004); online ed. 2008 accessed 20 June 2014 doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/14740

- Gash, Norman. "Lord Liverpool: a private view," History Today (1980) 30#5 pp 35–40

- Hay, William Anthony. Lord Liverpool: A Political Life (The Boydell Press, 2018).

- Hilton, Boyd. A Mad, Bad, and Dangerous People? England 1783–1846 (New Oxford History of England) (2006) scholarly survey

- Hutchinson, Martin (2008). Great Conservatives. Academica Press. pp. 28–32. ISBN 9781930901865.

- Hilton, Boyd. "The Political Arts of Lord Liverpool." Transactions of the Royal Historical Society (Fifth Series) 38 (1988): 147–170. online

- Hutchinson, Martin. Britain's Greatest Prime Minister: Lord Liverpool (Cambridge, The Lutterworth Press, 2020).

- Petrie, Charles. Lord Liverpool and His Times (1954)

- Plowright, John. Regency England: The Age of Lord Liverpool (Routledge, 1996) "The Lancaster Pamphlets".

- Sack, James J. The Grenvillites, 1801–29: Party Politics and Factionalism in the Age of Pitt and Liverpool (1991)

- Seton-Watson, R. W. Britain in Europe (1789–1914): A Survey of Foreign Policy (1937) online free

- Robertson, Tom. Lord Liverpool: A Reappraisal of the First Conservative Prime Minister.

- https://archives.blog.parliament.uk/2020/06/02/the-queen-caroline-affair/

External links

[edit]- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by the Earl of Liverpool

- Earl of Liverpool Prime Minister's Office (archived 12 November 2008)

- "Earl of Liverpool" by Prime Minister's Office (archived 12 November 2008)

- Portraits of Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- "Archival material relating to Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool". UK National Archives.

- Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool

- 1770 births

- 1828 deaths

- 19th-century prime ministers of the United Kingdom

- Alumni of Christ Church, Oxford

- British MPs 1790–1796

- British MPs 1796–1800

- British Secretaries of State for Foreign Affairs

- Earls of Liverpool (1796 creation)

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Knights of the Garter

- Lords Warden of the Cinque Ports

- Masters of the Mint

- Members of the Parliament of Great Britain for English constituencies

- Members of the Privy Council of Great Britain

- Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for English constituencies

- People educated at Charterhouse School

- People from Westminster

- Secretaries of State for the Home Department

- Secretaries of State for War and the Colonies

- Tory MPs (pre-1834)

- UK MPs 1801–1802

- UK MPs 1802–1806

- UK MPs who inherited peerages

- Commissioners of the Treasury for Ireland

- Tory prime ministers of the United Kingdom

- Leaders of the House of Lords

- British people of Indian descent

- British people of Portuguese descent

- Deaths from cerebrovascular disease