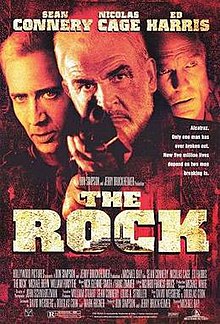

The Rock (film)

| The Rock | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Michael Bay |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by |

|

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | John Schwartzman |

| Edited by | Richard Francis-Bruce Steven Weisberg |

| Music by | |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Buena Vista Pictures Distribution |

Release date |

|

Running time | 136 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $75 million[2] |

| Box office | $335.6 million[2] |

The Rock is a 1996 American action thriller film directed by Michael Bay, produced by Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer, with a screenplay by David Weisberg, Douglas S. Cook and Mark Rosner. It stars Sean Connery, Nicolas Cage and Ed Harris, with supporting roles played by Michael Biehn, William Forsythe, David Morse, and John Spencer.

In the film, the Pentagon assigns a team comprising an FBI chemist and a former SAS captain with a team of SEALs to break into Alcatraz, where a rogue general and a rogue group of Force Recon Marines have seized all the tourists on the island and have threatened to launch rockets filled with nerve gas upon San Francisco unless the U.S. government pays $100 million to the next-of-kin of 83 men who were killed on missions that the general led and that the Pentagon denied.

The Rock was dedicated to the memory of co-producer Don Simpson,[3] who died five months before its release. The film was released by Buena Vista Pictures Distribution on June 7, 1996. It received positive reviews from critics, and was nominated for Best Sound at the 69th Academy Awards. It was also a financial success, earning box-office receipts of over $335 million against a production budget of $75 million, and became the fourth highest-grossing film of 1996. It was remade in India as Qayamat: City Under Threat.[4][5]

Plot[edit]

Disillusioned U.S. Brigadier General Francis Hummel and his second-in-command Major Tom Baxter lead a group of rogue Force Recon Marines in stealing fifteen M55 rockets filled with VX poison gas, a potent chemical weapon capable of killing any living organism in seconds. The next day, Hummel and his men seize control of Alcatraz Island, taking the tourists and guards hostage. He threatens to launch the rockets at San Francisco unless the U.S. government pays him $100 million from a covert slush fund, which he will distribute to his men and the families of the 83 Recon Marines who died on convert missions under his command, but whose sacrifices were not compensated, honored, or acknowledged.

The Department of Defense and the FBI plot to retake the island using a U.S. Navy SEAL team led by Commander Anderson, FBI chemical weapons specialist Dr. Stanley Goodspeed, and elderly British former SAS captain John Mason. The only man to escape Alcatraz, Mason has been imprisoned for three decades, disavowed by the British government, and his existence concealed by the FBI. FBI Director James Womack deceives Mason with the offer of a pardon and acquiesces to his request to move to a hotel, from which Mason escapes. After Mason leads the FBI on a destructive car chase through San Francisco, Goodspeed finds him meeting with his estranged daughter Jade. As the FBI arrives, Mason expresses his regret to her for not being in her life. At the mission command center, Mason negotiates to join the team on Alcatraz, while Goodspeed fails to convince his pregnant girlfriend Carla not to travel to San Francisco.

The team infiltrates Alcatraz, but Hummel's men are alerted to their presence and ambush them in a shower room. Hummel tries to convince Anderson to surrender, but his new allies, Captains Darrow and Frye, deliberately cause a shootout which kills Anderson's team, except for Mason and Goodspeed who remain undetected. Believing the mission a failure, Mason prepares to leave until Goodspeed reveals the truth about the VX, which also threatens Jade.

Mason and Goodspeed disable twelve of the rockets, during which Goodspeed is forced to kill a Marine, his first time killing someone. After Hummel threatens to execute a hostage, Mason surrenders to stall him while Goodspeed disables another rocket before also being captured. After Mason frees himself and Goodspeed, he reveals that he was an MI6 operative tasked with stealing a microfilm created by J. Edgar Hoover containing secrets of high profile global figures and classified U.S. information, including the Roswell incident. Mason refused to reveal the microfilms location after being captured, knowing he would be killed, and was imprisoned without trial. Having assessed Hummel as an honorable soldier who will not kill innocents, Mason leaves but returns to save Goodspeed, not wanting his child to grow up without a father.

The ransom deadline passes, leading Darrow and Frye to pressure Hummel into firing a rocket, but he redirects it to detonate harmlessly in the sea. Hummel explains the rockets were a bluff and he never intended to kill anyone, declaring the mission over. Realizing they will not be paid, Darrow and Frye kill Baxter and mortally wound Hummel, who tells Goodspeed the location of the last rocket before dying. Meanwhile, an airstrike is initiated to blanket Alcatraz with experimental thermite plasma bombs, which will neutralize the gas and incinerate everyone on the island. Goodspeed and Mason kill the remaining Marines, including Darrow and Frye, before signalling to abort the attack, but not before one bomb is dropped. The blast throws Goodspeed into the bay, but Mason saves him.

Goodspeed remotely confirms the missions success but claims that Mason was vaporized in the blast. The pair part ways amicably after Mason recommends Goodspeed take a trip to Fort Walton, Kansas. Sometime later, the now-married Goodspeed and Carla hastily drive away from a Kansas church after recovering the microfilm. Goodspeed asks Carla if she wants to know who really killed JFK.

Cast[edit]

- Sean Connery as Captain (retired) John Patrick Mason SAS/MI6

- Nicolas Cage as Dr. Stanley Goodspeed, FBI

- Ed Harris as General Francis X. Hummel, USMC

- Michael Biehn as Commander Anderson, USN

- William Forsythe as Ernest Paxton, FBI

- David Morse as Major Tom Baxter, USMC

- John Spencer as FBI Director James Womack

- John C. McGinley as Captain Hendrix, USMC

- Tony Todd as Captain Darrow, USMC

- Bokeem Woodbine as Sergeant Crisp, USMC

- Danny Nucci as Lieutenant Shepard, USN

- Claire Forlani as Jade Angelou, Mason's daughter

- Vanessa Marcil as Carla Pestalozzi, Goodspeed's fiancee

- Gregory Sporleder as Captain Frye, USMC

Uncredited members of the cast include Stuart Wilson as General Al Kramer; Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff,[6][7] David Marshall Grant as White House Chief of Staff Hayden Sinclair,[8][7] Philip Baker Hall as the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court,[6][7] Xander Berkeley as FBI technician Lonner,[7] and Stanley Anderson as the President of the United States.[7][9]

Other actors in smaller roles include Todd Louiso as FBI agent Marvin Isherwood, David Bowe as Dr. Ling, Howard Platt as Louis Lindstrom, John Laughlin as General Peterson, Harry Humphries as Admiral Johansson, Willie Garson as Francis Reynolds, Anthony Clark as Paul the hairdresser, Tom Towles as an Alcatraz park ranger, and Anthony Guidera and Jim Caviezel as F-18 pilots.

Members of Hummel's USMC unit are played by Raymond Cruz (uncredited) as Sergeant Rojas,[7][10] Jim Maniaci as Private Scarpetti, Greg Collins as Private Gamble, Brendan Kelly as Private Cox, and Steve Harris as Private McCoy. Dennis Chalker (Dando) and Marshall R. Teague (Reigert) play members of Anderson’s SEAL team.

Production[edit]

Writing and pre-production[edit]

Jonathan Hensleigh participated in writing the script, which became the subject of a dispute with the Writers Guild of America. The spec script (by David Weisberg and Douglas Cook) was reworked by several writers, but other than the original team, Mark Rosner was the only one granted official credit by guild arbitration. The rule is that the credited writing team must contribute 50% of the final script (effectively limiting credits to the screenplay's initial authors, plus one re-write team). Despite his work on the script, Hensleigh was not credited in the film. Michael Bay wrote an open letter of protest, in which he criticized the arbitration procedure as a "sham" and a "travesty". He said Hensleigh had worked closely with him on the movie and should have received screen credit.[11]

Quentin Tarantino and Aaron Sorkin were also an uncredited script doctors.[12]

British screenwriting team Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais were brought in at Connery's request to rewrite his lines, but ended up altering much of the film's dialogue.[13]

Casting[edit]

At one point, Arnold Schwarzenegger was to have played the role of Goodspeed. Schwarzenegger turned the role down because he did not like the script.[14]

Filming[edit]

Most of the film was shot on location in the Alcatraz Prison on Alcatraz Island. As it is governed by the National Park Service, it was not possible to close down Alcatraz, and much of the filming had to accommodate tour parties milling around.[15] The scene in which FBI Director Womack is thrown off the balcony was filmed on location at the Fairmont Hotel in San Francisco. The filming led to numerous calls to the hotel by people who saw a man dangling from the balcony.[16] The film's closing scene was shot outside the historic Sacred Heart Mission Church in Saticoy, California.[17]

This was Bay's first movie to be shot in a widescreen 2.39:1 aspect ratio, via Super 35. On the commentary track for the Criterion Collection DVD of Armageddon, Bay recalls not liking the format, due to the quality of the release prints, and did not touch the format again until Bad Boys II, at which point the digital intermediate process was available.[18]

There were tensions during shooting between director Bay and Walt Disney Studios executives who were supervising the production. On the commentary track for the Criterion Collection DVD, Bay recalls a time when he was preparing to leave the set for a meeting with the executives when he was approached by Sean Connery in golfing attire.[19] Connery, who also produced the film, asked Bay where he was going, and when Bay explained he had a meeting with the executives, Connery asked if he could accompany him. Bay complied and when he arrived in the conference room, the executives' jaws dropped when they saw Connery appear behind him. According to Bay, Connery then stood up for Bay and insisted that he was doing a good job and should be left alone.[20]

Music[edit]

The soundtrack to The Rock was released on the same day as the film, June 7, 1996, by Hollywood Records. Hans Zimmer and his longtime collaborator Nick Glennie-Smith were the principal composers, while Harry Gregson-Williams[21][22] was the score producer, with additional music composed by Don Harper, Steven M. Stern and Gregson-Williams.[23] The film represents the first collaboration between Zimmer and Bay, the composer would write and/or produce the scores for many of Bay’s film moving forward.

Reception[edit]

Box office[edit]

For its opening weekend, the film grossed $25 million, beating out Mission: Impossible to reach the number one spot.[24] It would be overtaken by The Cable Guy during its second weekend.[25] Produced on a $75 million budget, The Rock grossed a total of $134 million in the U.S. and Canada and $201 million elsewhere, for a worldwide total of $335 million.[26] It was the seventh-highest-grossing film for the U.S. box office in 1996, and the fourth highest-grossing U.S. film worldwide that year.[2]

Critical response[edit]

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 67% based on 72 reviews, with an average rating of 6.6/10. The website's critics consensus reads: "For visceral thrills, it can't be beat. Just don't expect The Rock to engage your brain."[27] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 58 out of 100, based on 24 critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[28] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A" on an A+ to F scale.[29]

Roger Ebert awarded the film 3.5 out of 4 stars, praising it as "a first-rate, slam-bang action thriller with a lot of style and no little humor".[30] Todd McCarthy of Variety gave the film a positive review, commenting "The yarn has its share of gaping holes and jaw-dropping improbabilities, but director Michael Bay sweeps them all aside with his never-take-a-breath pacing."[31] Richard Corliss, writing for the Time expressed favorable opinions towards the film, saying "Slick, brutal and almost human, this is the team-spirit action movie Mission: Impossible should have been."[32]

Accolades[edit]

The Rock won several minor awards, including 'Best On-Screen Duo' for Connery and Cage at the MTV Movie Awards. It was also nominated for an Academy Award for Best Sound (Kevin O'Connell, Greg P. Russell and Keith A. Wester).[33]

The film was selected for a limited edition DVD release by the Criterion Collection, a distributor of primarily arthouse films it categorizes as "important classic and contemporary films" and "cinema at its finest". In an essay supporting the selection of The Rock, Roger Ebert, who was strongly critical of most of Bay's later films, gave the film 3 1/2 out of four stars, calling it "an action picture that rises to the top of the genre because of a literate, witty screenplay and skilled craftsmanship in the direction and special effects."[34]

In 2014, Time Out polled several film critics, directors, actors and stunt actors to list their top action films.[35] The Rock was listed at 74th place on the list.[36]

In 2019, Tom Reimann from Collider ranked The Rock as Michael Bay's best film: "The Rock is not only Michael Bay's finest film, it's also a perfect snapshot of the height of 90s action movies."[37]

Controversies[edit]

Censorship[edit]

In the original UK DVD release, the scene in which Connery throws a knife through Scarpetti's throat and says "you must never hesitate" to Cage was cut, although the scene was shown on British television.[38] Consequently, a later scene in which Connery says to Cage, "I'm rather glad you didn't hesitate too long," lost its impact on viewers who had not seen the first scene. Other cuts included the reduction of gunshot impacts into Gamble's feet in the morgue down to a single hit; a close-up of his screaming face as the air conditioner falls onto him; a sound cut to Mason snapping a Marine's neck and two bloody gunshot wounds (to Hummel and Baxter), both near the end of the film.[38]

Iraqi chemical weapons program[edit]

A scene from the film was the basis for incorrect and false descriptions of the Iraqi chemical weapons program. Britain's Secret Intelligence Service was led to believe Saddam Hussein was continuing to produce weapons of mass destruction by a false agent who based his reports on the movie, according to the Chilcot Inquiry.[39]

In September 2002, MI6 chief Sir Richard Dearlove said the agency had acquired information from a new source revealing that Iraq was stepping up production of chemical and biological warfare agents. The source, who was said to have "direct access", claimed senior staff were working seven days a week while the regime was concentrating a great deal of effort on the production of anthrax. Dearlove told the chairman of the Joint Intelligence Committee (JIC), Sir John Scarlett, that they were "on the edge of (a) significant intel breakthrough" which could be the "key to unlock" Iraq's weapons programme.

However, questions were raised about the agent's claims when it was noticed his description bore a striking resemblance to a scene from the film. "It was pointed out that glass containers were not typically used in chemical munitions, and that a popular movie (The Rock) had inaccurately depicted nerve agents being carried in glass beads or spheres," the Chilcot report stated. By February 2003 – a month before the invasion of Iraq – MI6 concluded that their source had been lying "over a period of time" but failed to inform No 10 or others, even though Prime Minister Tony Blair had been briefed on this intelligence.[40][41][42] According to The Independent, the false claims of weapons of mass destruction were the justification for UK's entering the war.[42]

The film's co-writer David Weisberg said, "What was so amazing was anybody in the poison gas community would immediately know that this was total bullshit – such obvious bullshit". Weisberg said he was unsurprised a desperate agent might resort to films for inspiration, but dismayed that authorities "didn't do apparently the most basic fact-checking or vetting of the information. If you'd just asked a chemical weapons expert, it would have been immediately obvious it was ludicrous". Weisberg said he had had some "funny emails" after the report, but he felt "it's not a nice legacy for the film". "It's tragic that we went to war," he concluded.[43]

Unproduced sequel[edit]

In June 2017, director Michael Bay discussed his idea for a follow-up to The Rock that never developed past the concept that Goodspeed and Mason are chased by the government after escaping, due to possession of the microfilm as shown in the ending.[44]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "The Rock (15)". British Board of Film Classification. June 4, 1996. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- ^ a b c "The Rock (1996)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 10, 2019. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (June 7, 1996). "FILM REVIEW;Break into Alcatraz? Why Not?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 25, 2020. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ^ India Today. Thomson Living Media India Limited. July 2003.

- ^ "'Qayamat: City Under Threat' copied from 'The Rock'". Bollywood Copy - Not everything is original in Bollywood. August 8, 2017. Archived from the original on December 28, 2021. Retrieved December 28, 2021.

- ^ a b "'The Rock' Turns 20 But Remains Lovably Juvenile | Decider". June 7, 2016. Retrieved June 19, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f The Rock (1996) - Michael Bay | Cast and Crew | AllMovie. Retrieved June 19, 2024 – via www.allmovie.com.

- ^ nyfa. "How David Marshall Grant's Persistence Led to His Success". NYFA. Retrieved June 19, 2024.

- ^ Petski, Denise (June 28, 2018). "Stanley Anderson Dies: 'Spider-Man' & 'Seinfeld' Actor Was 78". Deadline. Retrieved June 19, 2024.

- ^ Hermanns, Grant (February 8, 2023). "Raymond Cruz On His Breaking Bad Return In PopCorners Super Bowl Ad". ScreenRant. Retrieved June 19, 2024.

- ^ Welkos, Robert W. "'Cable,' 'Rock' in Disputes on Writing Credits" Archived August 31, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. Los Angeles Times, May 21, 1996, p. 1.

- ^ Peary, Gerald (August 1998). "Chronology". Quentin Tarantino Interviews. Conversations with Filmmakers Series. University Press of Mississippi. xix. ISBN 1-57806-050-8. Archived from the original on April 30, 2016. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ Brew, Simon (October 2, 2020). "The Rock: the crucial rewrite that got Sean Connery on board". Film Stories. Retrieved February 23, 2023.

- ^ Arnold Schwarzenegger Interview / 22.01.13 / (San) Part 2 on YouTube

- ^ "The Rock 1996". Movie-Locations. Archived from the original on December 13, 2018. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- ^ Graff, Amy (October 1, 2019). "The untold stories of San Francisco's Fairmont Penthouse". SFGATE. Retrieved February 23, 2023.

- ^ Ritsch, Massie (June 17, 1999). "Out of the Picture?". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 8, 2021. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

- ^ Bay, Michael (director) (April 20, 1999). "Audio commentary". Armageddon (DVD). Vol. 40. The Criterion Collection.

- ^ Bay, Michael (director) (March 13, 2001). "Audio commentary". The Rock (DVD). Vol. 108. The Criterion Collection.

- ^ Bay, Michael (November 1, 2020). "Michael Bay Pens Tribute to Sean Connery and His "James Bond Smile" of Approval". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved February 23, 2023.

- ^ "An interview with Hans Zimmer". industrycentral.net. Archived from the original on January 9, 2017. Retrieved May 24, 2016.

- ^ "The Rock Soundtrack". filmscoremonthly.com. Archived from the original on September 24, 2020. Retrieved May 24, 2016.

- ^ ""The Rock" at Hans-Zimmer.com". Archived from the original on March 26, 2014. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- ^ "The Rock' rolls at U.S. box office". United Press International. June 10, 1996. Archived from the original on February 26, 2022. Retrieved February 26, 2022.

- ^ "First-place finish doesn't tell story". The Star Press. June 18, 1996. p. 9. Archived from the original on May 6, 2023. Retrieved May 6, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Brennan, Judy (June 10, 1996). "The Rock Rolls to $23-Million Opening". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ "The Rock". Rotten Tomatoes. November 24, 2013. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved June 15, 2022.

- ^ "The Rock Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on March 8, 2020. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- ^ "ROCK, THE". CinemaScore. Archived from the original on December 20, 2018.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (June 7, 1996). "The Rock Movie Review & Film Summary (1996)". www.rogerebert.com. Archived from the original on January 31, 2018. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (June 3, 1996). "Review: 'The Rock'". Variety. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved November 24, 2013.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (June 10, 1996). "Cinema: Good Rockin': Finally, summer has a smart, almost human action movie". Time. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved November 24, 2013.

- ^ "The 69th Academy Awards (1997) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. March 24, 1997. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ Roger Ebert (March 12, 2001). "The Rock". The Criterion Collection. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ^ "The 100 best action movies". Time Out. Archived from the original on November 6, 2014. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- ^ "The 100 best action movies: 80-71". Time Out. Archived from the original on November 7, 2014. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- ^ Reimann, Tom (December 13, 2019). "Every Michael Bay Movie Ranked from Worst to Best". Collider. Archived from the original on December 14, 2019. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ a b "Later DVDs merged into the Video Hits section". The Melon Farmers. Archived from the original on October 23, 2012. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ Kim, Sengupta (July 7, 2016). "Chilcot report: MI6 may have got crucial intelligence on Iraq WMDs from a Nicolas Cage film". The Independent. London, UK. Archived from the original on July 10, 2016. Retrieved January 4, 2023.

- ^ Walker, Peter (July 6, 2016). "The Rock movie plot 'may have inspired MI6 source's Iraqi weapons claim'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 7, 2016. Retrieved June 30, 2017.

- ^ "MI6 Iraq nerve gas report 'stolen from action film The Rock'". The Telegraph. July 6, 2016. Archived from the original on April 6, 2017. Retrieved June 30, 2017.

- ^ a b "Supposed Iraqi WMD described in dossier resembled inaccurate portrayal in Holywood film The Rock, Chilcot notes". The Independent. July 6, 2016. Archived from the original on May 17, 2017. Retrieved June 30, 2017.

- ^ Shoard, Catherine (July 8, 2016). "'It was such obvious bullshit': The Rock writer shocked film may have inspired false WMD intelligence". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 26, 2016. Retrieved June 30, 2017.

- ^ "The Rock Sequel Idea". /Film. June 20, 2017. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

External links[edit]

- The Rock at IMDb

- The Rock at AllMovie

- The Rock at Metacritic

- The Rock at Box Office Mojo

- The Rock at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Rock an essay by Roger Ebert at the Criterion Collection

- 1996 films

- 1996 action thriller films

- 1990s buddy films

- 1990s English-language films

- 1990s prison films

- Alcatraz Island in fiction

- American action thriller films

- American buddy action films

- American prison films

- Films about bomb disposal

- Films about chemical war and weapons

- Films about the Federal Bureau of Investigation

- Films about hostage takings

- Films about terrorism in the United States

- Films about the United States Marine Corps

- Films about United States Navy SEALs

- Films directed by Michael Bay

- Films produced by Don Simpson

- Films produced by Jerry Bruckheimer

- Films scored by Nick Glennie-Smith

- Films scored by Hans Zimmer

- Films set in the San Francisco Bay Area

- Films set in Virginia

- Films set in Washington, D.C.

- Films set on islands

- Films shot in Los Angeles

- Films shot in San Francisco

- Films shot in Ventura County, California

- Films with screenplays by Douglas S. Cook

- Films with screenplays by David Weisberg

- Hollywood Pictures films

- Jerry Bruckheimer Films films

- 1990s American films

- English-language action thriller films