Literary modernism

| Modernism | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins | 19th-century Europe |

| Cultural origins | Industrial Revolution |

| Subgenres | |

| Local scenes | |

| Literature | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Oral literature | ||||||

| Major written forms | ||||||

|

||||||

| Prose genres | ||||||

|

||||||

| Poetry genres | ||||||

|

||||||

| Dramatic genres | ||||||

| History | ||||||

| Lists and outlines | ||||||

| Theory and criticism | ||||||

|

| ||||||

Modernist literature originated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and is characterised by a self-conscious separation from traditional ways of writing in both poetry and prose fiction writing. Modernism experimented with literary form and expression, as exemplified by Ezra Pound's maxim to "Make it new."[1] This literary movement was driven by a conscious desire to overturn traditional modes of representation and express the new sensibilities of the time.[2] The immense human costs of the First World War saw the prevailing assumptions about society reassessed,[3] and much modernist writing engages with the technological advances and societal changes of modernity moving into the 20th century. In Modernist Literature, Mary Ann Gillies notes that these literary themes share the "centrality of a conscious break with the past", one that "emerges as a complex response across continents and disciplines to a changing world".[4]

Modernism, Romanticism, Philosophy and Symbol

[edit]Literary modernism is often summed up in a line from W. B. Yeats: "Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold" (in 'The Second Coming').[5] Modernists often search for a metaphysical 'centre' but experience its collapse.[6] (Postmodernism, by way of contrast, celebrates that collapse, exposing the failure of metaphysics, such as Jacques Derrida's deconstruction of metaphysical claims.)[7]

Philosophically, the collapse of metaphysics can be traced back to the Scottish philosopher David Hume (1711–1776), who argued that we never actually perceive one event causing another. We only experience the 'constant conjunction' of events, and do not perceive a metaphysical 'cause'. Similarly, Hume argued that we never know the self as object, only the self as subject, and we are thus blind to our true natures.[8] Moreover, if we only 'know' through sensory experience—such as sight, touch and feeling—then we cannot 'know' and neither can we make metaphysical claims.

Thus, modernism can be driven emotionally by the desire for metaphysical truths, while understanding their impossibility. Some modernist novels, for instance, feature characters like Marlow in Heart of Darkness or Nick Carraway in The Great Gatsby who believe that they have encountered some great truth about nature or character, truths that the novels themselves treat ironically while offering more mundane explanations.[9] Similarly, many poems of Wallace Stevens convey a struggle with the sense of nature's significance, falling under two headings: poems in which the speaker denies that nature has meaning, only for nature to loom up by the end of the poem; and poems in which the speaker claims nature has meaning, only for that meaning to collapse by the end of the poem.

Modernism often rejects nineteenth century realism, if the latter is understood as focusing on the embodiment of meaning within a naturalistic representation. At the same time, some modernists aim at a more 'real' realism, one that is uncentered. Picasso's proto-cubist painting, 'The Poet' of 1911 is decentred, presenting the body from multiple points of view. As the Peggy Guggenheim Collection website puts it, 'Picasso presents multiple views of each object, as if he had moved around it, and synthesizes them into a single compound image'.[10] This avoids the limitations of a single, privileged viewer, and points towards a more objective realism. Similarly, it has been argued that Wallace Stevens's realism

"serves a truth that is revealing—not the truth that prevails. It also is a “realism” that recognizes multiple perspectives, multiple truths. Perhaps the snow is not just white; it is also turning black, attuned to the menacing storm in the sky—or it is perhaps purple, surrounding a man with a monarch’s boundless ego."[11]

Modernism, with its sense that 'things fall apart,' can be seen as the apotheosis of romanticism, if romanticism is the (often frustrated) quest for metaphysical truths about character, nature, a higher power and meaning in the world.[12] Modernism often yearns for a romantic or metaphysical centre, but later finds its collapse.

This distinction between modernism and romanticism extends to their respective treatments of 'symbol'. The romantics at times see an essential relation (the 'ground') between the symbol (or the 'vehicle', in I.A. Richards's terms)[13] and its 'tenor' (its meaning)—for example in Coleridge's description of nature as 'that eternal language which thy God / Utters'.[14] But while some romantics may have perceived nature and its symbols as God's language, for other romantic theorists it remains inscrutable. As Goethe (not himself a romantic) said, ‘the idea [or meaning] remains eternally and infinitely active and inaccessible in the image’.[15] This was extended in modernist theory which, drawing on its symbolist precursors, often emphasizes the inscrutability and failure of symbol and metaphor. For example, Wallace Stevens seeks and fails to find meaning in nature, even if he at times seems to sense such a meaning. As such, symbolists and modernists at times adopt a mystical approach to suggest a non-rational sense of meaning.[16]

For these reasons, modernist metaphors may be unnatural, as for instance in T.S. Eliot's description of an evening 'spread out against the sky / Like a patient etherized upon a table'.[17] Similarly, for many later modernist poets nature is unnaturalized and at times mechanized, as for example in Stephen Oliver's image of the moon busily 'hoisting' itself into consciousness.[18]

Origins and precursors

[edit]In the 1880s, increased attention was given to the idea that it was necessary to push aside previous norms entirely, instead of merely revising past knowledge in light of contemporary techniques. The theories of Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) and Ernst Mach (1838–1916) influenced early Modernist literature. Ernst Mach argued that the mind had a fundamental structure, and that subjective experience was based on the interplay of parts of the mind in The Science of Mechanics (1883). Freud's first major work was Studies on Hysteria (with Josef Breuer; 1895). According to Freud, all subjective reality was based on the play of basic drives and instincts, through which the outside world was perceived. As a philosopher of science, Ernst Mach was a major influence on logical positivism, and through his criticism of Isaac Newton, a forerunner of Albert Einstein's theory of relativity.

Many prior theories about epistemology argued that external and absolute reality could impress itself, as it were, on an individual—for example, John Locke's (1632–1704) empiricism, which saw the mind beginning as a tabula rasa, a blank slate (An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, 1690). Freud's description of subjective states, involving an unconscious mind full of primal impulses and counterbalancing self-imposed restrictions, was combined by Carl Jung (1875–1961) with the idea of the collective unconscious, which the conscious mind either fought or embraced. While Charles Darwin's work remade the Aristotelian concept of "man, the animal" in the public mind, Jung suggested that human impulses toward breaking social norms were not the product of childishness or ignorance, but rather derived from the essential nature of the human animal.[citation needed]

Another major precursor of modernism was Friedrich Nietzsche,[19] especially his idea that psychological drives, specifically the "will to power", were more important than facts, or things. Henri Bergson (1859–1941), on the other hand, emphasised the difference between scientific clock time and the direct, subjective, human experience of time.[20] His work on time and consciousness "had a great influence on twentieth-century novelists," especially those modernists who used the stream of consciousness technique, such as Dorothy Richardson for the book Pointed Roofs (1915), James Joyce for Ulysses (1922) and Virginia Woolf (1882–1941) for Mrs Dalloway (1925) and To the Lighthouse (1927).[21] Also important in Bergson's philosophy was the idea of élan vital, the life force, which "brings about the creative evolution of everything".[22] His philosophy also placed a high value on intuition, though without rejecting the importance of the intellect.[22] These various thinkers were united by a distrust of Victorian positivism and certainty.[citation needed] Modernism as a literary movement can also be seen as a reaction to industrialisation, urbanisation and new technologies.

Important literary precursors of modernism were Fyodor Dostoyevsky (1821–81) (Crime and Punishment (1866), The Brothers Karamazov (1880)); Walt Whitman (1819–92) (Leaves of Grass) (1855–91); Gustave Flaubert (1821–1880) (Madame Bovary (1856–57), Sentimental Education (1869), The Temptation of Saint Anthony (1874), Three Tales (1877), Bouvard et Pécuchet (1881)); Charles Baudelaire (1821–67) (Les Fleurs du mal), Rimbaud (1854–91) (Illuminations, 1874); Knut Hamsun (1859–1952) (Hunger, 1890); August Strindberg (1849–1912), especially his later plays, including the trilogy To Damascus 1898–1901, A Dream Play (1902), and The Ghost Sonata (1907).

Initially, some modernists fostered a utopian spirit, stimulated by innovations in anthropology, psychology, philosophy, political theory, physics and psychoanalysis. The poets of the Imagist movement, founded by Ezra Pound in 1912 as a new poetic style, gave modernism its early start in the 20th century,[24] and were characterized by a poetry that favoured a precision of imagery, brevity and free verse.[24] This idealism, however, ended with the outbreak of World War I, and writers created more cynical works that reflected a prevailing sense of disillusionment. Many modernist writers also shared a mistrust of institutions of power such as government and religion, and rejected the notion of absolute truths.

Modernist works such as T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land (1922) were increasingly self-aware, introspective, and explored the darker aspects of human nature.[25]

The term modernism covers a number of related, and overlapping, artistic and literary movements, including Imagism, Symbolism, Futurism, Vorticism, Cubism, Surrealism, Expressionism, and Dada.

Early modernist writers

[edit]Early modernist writers, especially those writing after World War I and the disillusionment that followed, broke the implicit contract with the general public that artists were the reliable interpreters and representatives of mainstream ("bourgeois") culture and ideas, and, instead, developed unreliable narrators, exposing the irrationality at the roots of a supposedly rational world.[26]

They also attempted to address the changing ideas about reality developed by Charles Darwin, Ernst Mach, Freud, Albert Einstein, Nietzsche, Bergson and others. From this developed innovative literary techniques such as stream-of-consciousness, interior monologue, as well as the use of multiple points-of-view. This can reflect doubts about the philosophical basis of realism, or alternatively an expansion of our understanding of what is meant by realism. For example, the use of stream-of-consciousness or interior monologue reflects the need for greater psychological realism.

It is debatable when the modernist literary movement began, though some have chosen 1910 as roughly marking the beginning and quote novelist Virginia Woolf, who declared that human nature underwent a fundamental change "on or about December 1910".[27] But modernism was already stirring by 1902, with works such as Joseph Conrad's (1857–1924) Heart of Darkness, while Alfred Jarry's (1873–1907) absurdist play Ubu Roi appeared even earlier, in 1896.

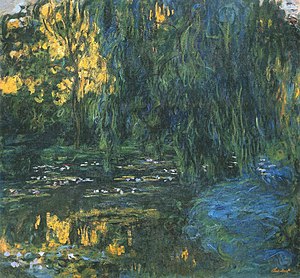

Among early modernist non-literary landmarks is the atonal ending of Arnold Schoenberg's Second String Quartet in 1908, the Expressionist paintings of Wassily Kandinsky starting in 1903 and culminating with his first abstract painting and the founding of the Expressionist Blue Rider group in Munich in 1911, the rise of fauvism, and the introduction of cubism from the studios of Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque and others between 1900 and 1910.

Sherwood Anderson's Winesburg, Ohio (1919) is known as an early work of modernism for its plain-spoken prose style and emphasis on psychological insight into characters.

James Joyce was a major modernist writer whose strategies employed in his novel Ulysses (1922) for depicting the events during a twenty-four-hour period in the life of his protagonist, Leopold Bloom, have come to epitomize modernism's approach to fiction. The poet T. S. Eliot described these qualities in 1923, noting that Joyce's technique is "a way of controlling, of ordering, of giving a shape and a significance to the immense panorama of futility and anarchy which is contemporary history.... Instead of narrative method, we may now use the mythical method. It is, I seriously believe, a step toward making the modern world possible for art."[28] Eliot's own modernist poem The Waste Land (1922) mirrors "the futility and anarchy" in its own way, in its fragmented structure, and the absence of an obvious central, unifying narrative. This is in fact a rhetorical technique to convey the poem's theme: "The decay and fragmentation of Western Culture".[29] The poem, despite the absence of a linear narrative, does have a structure: this is provided by both fertility symbolism derived from anthropology, and other elements such as the use of quotations and juxtaposition.[29]

In Italian literature, the generation of poets represented by Eugenio Montale (with his Ossi di seppia), Giuseppe Ungaretti (with his Allegria di naufragi), and Umberto Saba (with his Canzoniere) embodies modernism. This new generation broke with the tradition of Giosuè Carducci, Giovanni Pascoli, and Gabriele D'Annunzio in terms of style, language and tone. They were aware of the crisis deriving from the decline of the traditional role of the poet as foreseer, teacher, prophet. In a world that has absorbed Friedrich Nietzsche's lesson, these poets want to renew literature according to the new cultural world of the 20th century. For example, Montale uses epiphany to reconstruct meaning, while Saba incorporates Freudian concepts of psychoanalysis.[30]

Modernist literature addressed similar aesthetic problems as contemporary modernist art. Gertrude Stein's abstract writings, such as Tender Buttons (1914), for example, have been compared to the fragmentary and multi-perspective Cubist paintings of her friend Pablo Picasso.[31] The questioning spirit of modernism, as part of a necessary search for ways to make sense of a broken world, can also be seen in a different form in the Scottish poet Hugh MacDiarmid's A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle (1928). In this poem, MacDiarmid applies Eliot's techniques to respond to the question of nationalism, using comedic parody, in an optimistic (though no less hopeless) form of modernism in which the artist as "hero" seeks to embrace complexity and locate new meanings.[citation needed]

Regarding technique, modernist works sought to obfuscate the boundaries between genres. Thus, prose works tended to be poetical and poetry prose-like. T. S. Eliot's poetry sacrified lyrical grace for the sake of fragmented narrative while Virginia Woolf's novels (such as Mrs Dalloway and The Waves) have been described as poetical.

Other early modernist writers and selected works include:

- Knut Hamsun (1859–1952): Hunger (1890), Growth of the Soil (1917);

- Italo Svevo (1861–1928): Senilità (1898), Zeno's Conscience (1923);

- Luigi Pirandello (1867–1936): The Late Mattia Pascal (1904), Six Characters in Search of an Author (1921);

- Rainer Maria Rilke (1875–1926): The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge (1910), Sonnets to Orpheus (1922), Duino Elegies (1922);

- Guillaume Apollinaire (1880–1918): Alcools (1913);

- Andrei Bely (1880–1934): Petersburg (1913);

- Katherine Mansfield (1888–1923); Prelude (1918);

- Georg Trakl (1887–1914): Poems (1913);

- Franz Kafka (1883–1924): The Metamorphosis (1915), The Trial (1925), The Castle (1926);

- Dorothy Edwards (1902–34): Rhapsody (1927), Winter Sonata (1928);

- Konstantine Gamsakhurdia (1893–1975):The Smile of Dionysus (1925), Kidnapping the Moon (1935–1936), The Right Hand of the Grand Master (1939);

- Grigol Robakidze (1880–1962): The Snake's Skin (1926);

- Miroslav Krleža (1893–1981), Kristofor Kolumbo (1918), Michelangelo Buonarroti (1919), Povratak Filipa Latinovicza (1932);

- Wyndham Lewis (1882–1957): Tarr (1918);

- Hope Mirrlees (1887–1978): Paris: A Poem (1919);

- Karel Čapek (1890–1938): R.U.R. (1920);

- Ryūnosuke Akutagawa (1861–1928): "Hana" (1916); "Rashōmon" (1915); "In a Grove" (1922);

- André Gide (1869–1951): The Counterfeiters (1925)

Continuation: 1920s and 1930s

[edit]Significant modernist works continued to be created in the 1920s and 1930s, including further novels by Marcel Proust, Virginia Woolf, Robert Musil (The Man Without Qualities), and Dorothy Richardson. The American modernist dramatist Eugene O'Neill's career began in 1914, but his major works appeared in the 1920s and 1930s and early 1940s. Two other significant modernist dramatists writing in the 1920s and 1930s were Bertolt Brecht and Federico García Lorca. D. H. Lawrence's Lady Chatterley's Lover was published in 1928, while another important landmark for the history of the modern novel came with the publication of William Faulkner's The Sound and the Fury in 1929. The 1920s would prove to be watershed years in modernist poetry. In this period, T. S. Eliot published some of his most notable poetic works, including The Waste Land, The Hollow Men, and Ash Wednesday.

In the 1930s, in addition to further major works by William Faulkner (As I Lay Dying, Light in August), Samuel Beckett published his first major work, the novel Murphy (1938), while in 1932 John Cowper Powys published A Glastonbury Romance, the same year as Hermann Broch's The Sleepwalkers. In 1935 E. du Perron published his Country of Origin, the seminal work of Dutch modernist prose. Djuna Barnes published her novel Nightwood in 1936, the same year as Miroslav Krleža's Ballads of Petrica Kerempuh. Then in 1939 James Joyce's Finnegans Wake appeared. It was in this year that another Irish modernist, W. B. Yeats, died. In poetry, E. E. Cummings, and Wallace Stevens continued writing into the 1950s. It was in this period when T. S. Eliot began writing what would become his final major poetic work, Four Quartets. Eliot shifted focus in this period, writing several plays, including Murder in the Cathedral.

While modernist poetry in English is often viewed as an American phenomenon, with leading exponents including Ezra Pound, Hart Crane, Marianne Moore, William Carlos Williams, H.D., and Louis Zukofsky, there were important British modernist poets, including T. S. Eliot, David Jones, Hugh MacDiarmid, Basil Bunting, and W. H. Auden. European modernist poets include Federico García Lorca, Fernando Pessoa, Anna Akhmatova, Constantine Cavafy, and Paul Valéry.

Modernist literature after 1939

[edit]Though The Oxford Encyclopedia of British Literature sees Modernism ending by c. 1939,[32] with regard to British and American literature, "When (if) Modernism petered out and postmodernism began has been contested almost as hotly as when the transition from Victorianism to Modernism occurred".[33] Clement Greenberg sees Modernism ending in the 1930s, with the exception of the visual and performing arts.[34] In fact, many literary modernists lived into the 1950s and 1960s, though generally speaking they were no longer producing major works.[citation needed]

Late modernism

[edit]The term late modernism is sometimes applied to modernist works published after 1930.[32][35] Among modernists (or late modernists) still publishing after 1945 were Wallace Stevens, Gottfried Benn, T. S. Eliot, Anna Akhmatova, William Faulkner, Dorothy Richardson, John Cowper Powys, and Ezra Pound. Basil Bunting, born in 1901, published his most important modernist poem Briggflatts in 1965. In addition Hermann Broch's The Death of Virgil was published in 1945 and Thomas Mann's Doctor Faustus in 1947 (early works by Thomas Mann, The Magic Mountain (1924), and Death in Venice (1912) are sometimes considered modernist). Samuel Beckett, who died in 1989, has been described as a "later modernist".[36] Beckett is a writer with roots in the expressionist tradition of modernism, who produced works from the 1930s until the 1980s, including Molloy (1951), En attendant Godot (1953), Happy Days (1961) and Rockaby (1981). The terms minimalist and post-modernist have also been applied to his later works.[37] The poets Charles Olson (1910–1970) and J. H. Prynne (b. 1936) have been described as late modernists.[38]

More recently the term late modernism has been redefined by at least one critic and used to refer to works written after 1945, rather than 1930. With this usage goes the idea that the ideology of modernism was significantly re-shaped by the events of World War II, especially the Holocaust and the dropping of the atom bomb.[38] Taking this further, instead of attempting to impose some arbitrary 'end-date' on modernism, one may acknowledge the many writers after 1945 who resist easy inclusion into the category 'postmodern' and yet, heavily influenced by (say) American and/or European modernism, continued to manifest significant neo-modernist works, for instance Roy Fisher, Mario Petrucci and Jorge Amado. Another example of post-1945 modernism, then, would be the first modernist work of Reunionnais literature entitled Sortilèges créoles: Eudora ou l'île enchantée (fr), published 1952 by Marguerite-Hélène Mahé.[39][40]

Theatre of the Absurd

[edit]The term Theatre of the Absurd is applied to plays written by primarily European playwrights, that express the belief that human existence has no meaning or purpose and therefore all communication breaks down. Logical construction and argument gives way to irrational and illogical speech and to its ultimate conclusion, silence.[41] While there are significant precursors, including Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), the Theatre of the Absurd is generally seen as beginning in the 1950s with the plays of Samuel Beckett.

Critic Martin Esslin coined the term in his 1960 essay, "Theatre of the Absurd." He related these plays based on a broad theme of the Absurd, similar to the way Albert Camus uses the term in his 1942 essay, "The Myth of Sisyphus".[42] The Absurd in these plays takes the form of man's reaction to a world apparently without meaning, and/or man as a puppet controlled or menaced by invisible outside forces. Though the term is applied to a wide range of plays, some characteristics coincide in many of the plays: broad comedy, often similar to Vaudeville, mixed with horrific or tragic images; characters caught in hopeless situations forced to do repetitive or meaningless actions; dialogue full of clichés, wordplay, and nonsense; plots that are cyclical or absurdly expansive; either a parody or dismissal of realism and the concept of the "well-made play".

Playwrights commonly associated with the Theatre of the Absurd include Samuel Beckett (1906–1989), Eugène Ionesco (1909–1994), Jean Genet (1910–1986), Harold Pinter (1930–2008), Tom Stoppard (b. 1937), Alexander Vvedensky (1904–1941), Daniil Kharms (1905–1942), Friedrich Dürrenmatt (1921–1990), Alejandro Jodorowsky (b. 1929), Fernando Arrabal (b. 1932), Václav Havel (1936–2011) and Edward Albee (1928–2016).

See also

[edit]- Modernismo

- Modernist poetry

- Contemporary French literature

- Experimental literature

- Expressionism (theatre)

- History of theatre

- Sexology

- 20th century in literature

- Twentieth-century English literature

- Postmodern literature

- List of modernist writers

- List of modernist women writers

- List of modernist poets

References

[edit]- ^ Pound, Ezra, Make it New, Essays, London, 1935

- ^ Childs, Peter (2008). Modernism. Routledge. p. 4. ISBN 978-0415415460.

- ^ Morley, Catherine (March 1, 2012). Modern American Literature. EDINBURGH University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-7486-2506-2. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- ^ Gillies, Mary Ann (2007). Modernist Literature. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 2,3. ISBN 978-0748627646.

- ^ James Longenbach, for instance, quotes these words and says, 'What line could feel more central to our received notions of modernism?' in his chapter, 'Modern Poetry' in David Holdeman and Ben Levitas, W.B. Yeats in Context, (Cambridge: CUP, 2010), p.327. Longenbach quotes Cynthia Ozik, who said, 'That [i.e. this line], we used to think, was the whole of Modernism.... Now we know better, and also in a way worse. Yeats hardly foresaw how our dissolutions would surpass his own'. See Cynthia Ozick, 'The Muse, Postmodernism and Homeless', New York Times Book Review, 18 January 1987.

- ^ According to the Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy, Lyotard claims that 'Modern art is emblematic of a sublime sensibility, that is, a sensibility that there is something non-presentable demanding to be put into sensible form and yet overwhelms all attempts to do so'. See section 2 ('The Postmodern Condition') of the article on 'Postmodernism' at https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/postmodernism/#5.

- ^ See section 5 ('Deconstruction') in 'Postmodernism', Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/postmodernism/#5.

- ^ Hume says, 'For my part, when I enter most intimately into what I call myself, I always stumble on some particular perception or other, of heat or cold, light or shade, love or hatred, pain or pleasure. I never can catch myself at any time without a perception'. See A Treatise of Human Nature, Book I.iv, section 6.

- ^ Daphne Erdinast- Vulcan explores Conrad's relation to Modernism, Romanticism and metaphysics in Joseph Conrad and the Modern Temper, Oxford: OUP, 1991. David Lynn describes Nick Carraway as "A synthesis of disparate impulses whose roots lie in nineteenth-century Romanticism and Realism[.] Nick's heroism is borne out in his assuming responsibility for Gatsby and in the act of narration." See 'Within and Without: Nick Carraway', in: The Hero's Tale, chapter 4, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1989.

- ^ The painting is in the Peggy Guggenheim Collection. See: https://www.guggenheim-venice.it/en/art/works/the-poet/.

- ^ Quoted from the abstract to David Michael Kleinberg-Levin, "Wallace Stevens’ Poetic Realism: The Only Possible Redemption", in: Hagberg, G.L. (eds) Narrative and Ethical Understanding. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-58433-6_15

- ^ Schlegel, as an early German romantic, declared, "Only when striving toward truth and knowledge can a spirit be called a philosophical spirit". See '19th Century Romantic Aesthetics' in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. The idea of romanticism as an internalised quest is a commonplace. Harold Bloom, for instance, has written extensively on Romanticism as 'The Internalisation of Quest-Romance' in Romanticism and Consciousness, New York: Norton, 1970, pp.3–24.

- ^ I.A. Richards, The Philosophy of Rhetoric, (Oxford University Press: New York and London, 1936). Technically, Richards applies the terms 'vehicle' and 'tenor' to metaphor rather than symbol.

- ^ S.T. Coleridge, 'Frost at Midnight', https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43986/frost-at-midnight. On Coleridge, see Nicholas Reid, Coleridge, Form and Symbol (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006), pp.1–7.

- ^ Quoted by Nicholas Halmi in The Genealogy of the Romantic Symbol (Oxford: OUP, 2007), p.1.

- ^ Arthur Symons introduced the mystical aspect of Symbolism in his 1899 book, The Symbolist Movement in Literature, https://archive.org/details/symbolistmovemen00symouoft.

- ^ T.S. Eliot, 'The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock', https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/poems/44212/the-love-song-of-j-alfred-prufrock. Seamus Perry notes 'The play between the belated romanticism of an evening 'spread out against the sky' and the incongruous modernity of 'a patient etherised upon a table' in 'A close reading of The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock', on the British Library's website, https://www.bl.uk/20th-century-literature/articles/a-close-reading-of-the-love-song-of-j-alfred-prufrock Archived 7 August 2023 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Stephen Oliver, Cranial Bunker (Canberra: Greywacke Press, 2023), p.27.

- ^ Robert Gooding-Williams, "Nietzsche's Pursuit of Modernism" New German Critique, No. 41, Special Issue on the Critiques of the Enlightenment. (Spring – Summer, 1987), pp. 95–108.

- ^ Diané Collinson, Fifty Major Philosophers: A Reference Guide, p.131

- ^ The Bloomsbury Guides to English Literature: The Twentieth Century, ed. Linda R. Williams. London: Bloomsbury, 1992, pp. 108–9.

- ^ a b Collinson, 132.

- ^ David Thorburn, MIT, The Great Courses, The Teaching Company, 2007, Masterworks of Early 20th-Century Literature, see p. 12 of guidebook Part I, Accessed August 24, 2013

- ^ a b Pratt, William. The Imagist Poem, Modern Poetry in Miniature (Story Line Press, 1963, expanded 2001). ISBN 1-58654-009-2.

- ^ Modernism (1995). Merriam Webster's Encyclopedia of Literature. Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster. p. 1236.

- ^ Bossy 2001, p. 100.

- ^ Virginia Woolf. "Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown." Collected Essays. Ed. Leonard Woolf. Vol. 1. London: Hogarth, 1966. pages 319–337.

- ^ Eliot, T. S. (November 1923). "'Ulysses,' Order and Myth. Rev. of Ulysses by James Joyce". The Dial.

- ^ a b Bloomsbury Guides to English Literature: The Twentieth Century, ed. Linda R. Williams. London: Bloomsbury, 1992, p.311.

- ^ "Modernismo e poesia italiana del primo novecento". Le parole e le cose. November 30, 2012. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- ^ Dubnick, Randa K. (1984). The Structure of Obscurity: Gertrude Stein, Language, and Cubism. Champaign: University of Illinois Press. pp. 16–20. ISBN 0-252-00909-6.

- ^ a b J. H. Dettmar "Modernism" in The Oxford Encyclopedia of British Literature ed. by David Scott Kastan. Oxford University Press, 2006.

- ^ "modernism", The Oxford Companion to English Literature. Edited by Dinah Birch. Oxford University Press Inc. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Clement Greenberg: Modernism and Postmodernism Archived September 1, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, William Dobell Memorial Lecture, Sydney, Australia, October 31, 1979, Arts 54, No.6 (February 1980). His final essay on modernism. Retrieved October 26, 2011

- ^ Cheryl Hindrichs (November 2011). "Late Modernism, 1928–1945: Criticism and Theory". Literature Compass. 8 (11): 840–855. doi:10.1111/j.1741-4113.2011.00841.x.

- ^ Morris Dickstein (August 3, 1997). "An Outsider to His Own Life". The New York Times (Book review).

- ^ The Cambridge Companion to Irish Literature, ed. John Wilson Foster. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- ^ a b Late modernist poetics: From Pound to Prynne by Anthony Mellors; see also Prynne's publisher, Bloodaxe Books.

- ^ Rauville, Camille de (1990). Littératures francophones de l'océan Indien (in French). Editions du Tramail. ISBN 978-2-908344-05-9.

- ^ Christophe, SOLIOZ (December 1, 2003). Les esclaves de Bourbon -la mer et la montagne (in French). KARTHALA Editions. ISBN 978-2-8111-3781-6.

- ^ The Hutchinson Encyclopedia, Millennium Edition, Helicon 1999

- ^ "The Theatre Of The Absurd". Arts.gla.ac.uk. Archived from the original on August 23, 2009. Retrieved January 13, 2014.

Sources

[edit]- Baym, Nina. The Norton Anthology of American Literature. New York: W.W. Norton, 2007. Print.

- Bossy, Michel-André (2001). Artists, Writers, and Musicians: An Encyclopedia of People Who Changed the World. Westport, Connecticut: Oryx Press. ISBN 978-1-57356-154-9.

- Bryne, CJ. "Understanding Modernism and PostModernism" Writing.com

- Goldman, Jonathan. Modernism Is the Literature of Celebrity. Austin: U of Texas P, 2011. Print.

- "Modernism in Literature: What Is Modernism?" Bright Hub March 23, 2011..

- "Some Characteristics of Modernism in Literature" Fakultet for Sprog Og Erhvervskommunikation – Handelshøjskolen I Århus. March 23, 2011

- Literary modernism at Curlie

- Absurdist Monthly Review – The Writers Magazine of The New Absurdist Movement

- Picturing Literary Modernism Photographs of artistic and literary Americans at home and abroad throughout the Modernist period from the collection of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University

External links

[edit]- "Literary Modernism" BBC Radio 4 discussion with John Carey, Laura Marcus and Valentine Cunningham (In Our Time, April 26, 2001)